Rosendale Uncut

'Confessions of a Bar Brat'

Main Street's wildest days

Anne Pyburn Graig

BSFWriter

Rosendale is a singular place. Geography, history and

human migration; cement and canals, art and industry.

llou can travel far and wide and not discover anything

remotelylike it: trestle sunsets and squabbles, hospitality

and festive heart, in-your-face situations that lead to solutiong

even if it takes a minute.

And Rosendale, as those nrho study it larow, had an

intenselybad-ass centuryfrom around 1895 to 1g95. The

canal was gong the cement was fading and, to put the

icing on the cake, Main Street got repeatedlywrecked by

fuesandfloods.

During a particularly colorfi.rl part of

this era, alittle girl namedludyChemy

was going about serious kid business as

&e only daughter in the famity running

Reid's Hotel in the '50s. Itwas the kind

of place where therewas gamblingin

the basement, early drinking behind

closed doors on a Sunday, and plenty

of drink-fueled drama, along with the

vocalsrylings of "BigEdiwho could

move folks to tears (besides the bar, he

sang in St Peter's choir at funerals and

special occasions), and the carefi.rlly

calibrated flirtation and wit of Edie.

Big Ed and Edie were iconic to the

partying crowd and vilified by the

Respectable Citizens, and being their

daughter would have made for a terrifying;

exceedingly colorfr.rl childhood

for anyone. Ediewas hard-drinking and narcissistig Big

Ed was a loud violent perfectionist; running the bar consumed

them, and to saythe needs of their childrei got

put onthe backbumerwould be epic understatement.

Then, toq itwas the lg50s; free-range "come homewhen

it gets darP parentingwas still a cultural norm, albeit one

the Chemys tookto ertremes.

Howfortunatewe are that Big Ed and Edie created

Iudith. We meet her in a prologue, little brother Mickey

slung on her hip enduring the excmciating hurniliation

of her parents/ eviction &om Reid's place. Shet I I . And,

having been a Rosendale gal for a fewyears and having

watched this whole situation unfold, she haows exactly

where t9 go andwhat tojo.

_

"Conl'essions oI a t ar 6rat: Growing up in Rosendale,

NewYorh is an essential book " Some may not like it.

Iudy Chemy (now Judith Boggess, MSC and an acclaimed

poet, artist and clerglrwoman) names names and doesn't

vamish her truth. Even the Rosendale Theatre, nrtrich she

pretty much credits with saving her sanity, gets called ouq

from a kid's point of view, for being less &an tolerant of

preadolescentmessiness and foibles BackIn The Day.

Overall, little Judy makes Harriet the Spy look like a piker

in everyway -- she's irreverent as a bright, wounded child

could be, wi& an instinctive sense of justice that gets

trampled in the bar, the streetg and the classrooms and

confession booths of St. Peter's with equal brutality. As

she gets older, people getmoree4plicit in tellingher that

her family is "white faslf because they don't take care of

her much, but surprisingly fewwere willing to offer her

anythingbutblame and exclusion. Those fewshine inthe

telling.

The trulyamazingthing about Boggess- memoir is not

the sins of commission and omission committed by the

adults, but the perspective. Through her child-eyeg we

see not just the rottenness but the sweetness -- &e th-rill

of swinginghigh, themoviemagig &e time Ediepainted

the bar windows for Christnas, Big Ed explaining why

we don't cut ttre legs off a daddy-long-legs. It seems like

it couldn't have been enough, given the humiliations and

hard days and themidnight intruderwithhis hand in her

panties -- yet somehow, she took enough ftom the music

and art and moments of kindness, and Iuditih managed

to emerge. I admit I'd Hke to read a sequel that tells of her

teenage years and how she managed that, but it is satis$-

ing enough to have the storyendwith the greatflood of

1955,

In a townwhereToo Much Informationwas bom

and thrives, "Confessions of a Bar Brat'' splashes a bold

schmear of indelible inkinto &e annals of local history.

Ifyou love Rosendale, her people and her struggles, read

this for an intimate peek behind the curtain -- the blend

of critique and love letter cuts to the very quick. EE[l

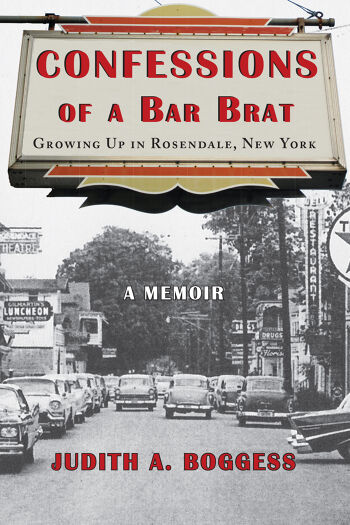

Boggess and

book cover

Verdict: CONFESSIONS OF A BAR BRAT evokes authentic, immediate conjuring of the terrors and wonders of one woman’s childhood that speaks to the child in all of us

4.5

In MEMOIRS OF A BAR BRAT, Judith A. Boggess works a time-traveler’s magic. Reading it, you feel as if you are racing with her down the streets of 1950s Rosedale, New York to watch the latest Jimmy Cagney film or help her brother catch eels in the local creek. But more than just the details of time and place, Boggess has recaptured perfectly the spirit of childhood: the openness to experience that makes the world sometimes more magical and sometimes infinitely more painful and lonely. It is hard to believe she wrote her book 67 years after she lived it.

Some of the indignities Boggess recounts are of the sort most former children can probably read with a wince and a chuckle of recognition. When young Judy learns that Jimmy Cagney does not really die when he dies in a film, for example, she is both humiliated by the laughter of the adults around her and strangely mournful for the loss of such a complete faith in cinema. But Boggess’ childhood was also uniquely painful in many ways. Her parents were physically abusive to each other and verbally abusive and neglectful towards her. There are, full warning, particularly traumatic events in her life that are difficult to read.

However, because Boggess does such a good job of showing the reader the world through young Judy’s eyes, these events are told with a child-like matter-of-factness and poetry that ease the raw brutality of the facts while enhancing their emotional impact. Of her parents’ repetitive fights, she writes, “It was like a movie script they kept rehearsing and couldn’t get right so ‘The End’ could flash across the screen.” The metaphor conveys the horror of the cycle of abuse in language that makes sense for a film-obsessed young dreamer, and it is all the more poignant for it.

CONFESSIONS OF A BAR BRAT also has moments of levity, often provided by Judy’s irrepressible spirit and unique outlook. Her memories of recreating Fred-and-Ginger dance routines with her best friend, designing Edith-Head inspired gowns for her paper dolls, rolling-skating next to cars in the street, and charging local children to hear her recite a minute’s worth of swear words without repeating herself, keep the reader turning the pages to join her in her next adventure. Boggess turns Judy into someone the reader enjoys spending time with, so that, when the harder moments come, they are willing to stay and face them through her eyes.

~Olivia Rosane for IndieReader

Memoir recalls growing up as a “bar brat” in Rosendale by Sharyn Flanagan/July 31, 2017

Share153

“Confessions of a Bar Brat” author Judith Boggess, Main Street in Rosendale. (photo: Lauren Thomas)

“I don’t think I understood just how abusive my childhood was until I started writing about it,” says Judith Boggess about her recently published memoir, “Confessions of a Bar Brat: Growing Up in Rosendale, New York” (2017, Epigraph Books).

In a colloquial dialect from her point of view as a young girl age six to 12, Boggess chronicles what life was like growing up in Rosendale in the 1940s and ‘50s as Judy Cherny, the daughter of hard-drinking Edith and mercurial “Big Ed,” who together ran one of the toughest bars on Main Street at Reid’s Hotel and Bar. Alternately neglected or abused, her life was one of constant chaos. Her only respite, really, was in her frequent visits to the Rosendale Theatre, where she found better role models for adulthood in the movies on the big screen than she did at home.

Boggess began writing down memories of her childhood at a time when she was working in a profession that brought her into contact with abused women and runaways. She had grown a bit tired of hearing certain comments from people unfamiliar with the nature of abuse, she says; things like, “Why doesn’t she just leave him if he’s so abusive?” or “Why didn’t the kid tell somebody?”

She knew from her own experiences that it isn’t that simple. “Children live what they learn, and act out on it. Some who are abused go into drugs or alcohol, or promiscuity, and others just succumb. All through their lives, they’re trying to patch themselves up. They feel like they’re broken, like something needs to be repaired.”

What began as “probably 7,000 pages” of memories, she jokes, was eventually edited into the current book of 420 pages. And like many memoirists before her, Boggess says she discovered that “once it gets out of your head, and on to paper, you can let it go.”

She never kept a diary during those childhood years, but says she has an excellent memory. She has an ear for dialogue, as well, the narrative peppered with colorful language that evokes a feeling of time and place and brings the reader decisively into the moment. And those who grew up in Rosendale themselves are sure to find much to relate to in her descriptions of the local scene and the early days of the Rosendale Theatre.

Promoting her book at the Rosendale Street Festival recently was an unnerving experience for her, one she likens to “riding through Main Street naked like Lady Godiva, but with short hair!” Sitting in her booth there, on the street where it all happened so long ago, made her feel like “the sidewalks were going to lift up around me like a horror show for having told the secrets of the town.”

Boggess says she chose to write the book from a child’s perspective because it was important to her that it not come across as “blaming, or shaming. It’s just what happened to me. And this is how I dealt with it.”

As an adult, she says, “Whenever my inner child was having a tantrum, I’d say to that child, ‘Look, I’m an adult now and I’m in charge. You can relax and I’ll take care of you.’ And somewhere along the line as I was writing, I thought, ‘I gotta give this kid inside a voice.’”

The story ends in 1955 with the great flood of Rosendale. Boggess has no plans to write a sequel, if for no other reason than she doesn’t want to put anything into print that might embarrass her daughters.

When asked if she could have written this book while her mother was alive, she says she could have. “For one thing, my mother would never have read it, and if she did, she’d just say, ‘this is BS.’” (Having read the book, this sounds about right.)

In speaking with Boggess today, one would never think she had lived through a childhood so challenging. She laughs often, and easily. Her compassion for others comes across clearly and she has a spiritual outlook about the world based on Native American traditions — with a dash of Buddhism — that grounds her. Her status within the local Native American community as “Grandmother Judith Laughing Owl, Keeper of the Women’s Drum” gives her joy, as does painting in oils, primarily of Native American subject matter.

As an active member of the Association of Native Americans of the Hudson Valley, Boggess sings with the Red Feather Singers at schools and historical societies, and keeps the sacred drum belonging to the women of the association at her home, where she teaches drumming. After a genealogy search revealed she is part Cherokee, Boggess taught herself to speak a bit of the language, and she translated “Silent Night” and “Amazing Grace” into Cherokee for the Red Feather Singers to perform.

And she is passionate about continuing to work on her painting, currently doing a series based on Edward S. Curtis photographs of Native Americans and another series on Native American chiefs she knows. Boggess isn’t selling the original oils at this time, but the images are available in limited editions of 10 as giclée prints.

As of press time, “Confessions of a Bar Brat: Growing Up in Rosendale, New York” is available locally at Inquiring Minds book store in New Paltz and the Golden Notebook in Woodstock, where she did a reading from the book last Sunday. A reading at the Rosendale Library is set for November 29 at 7 p.m., and she will likely visit other venues to do readings before then as scheduled. More information is available at www.JudithBoggessArtist.com.