Doctor Pluss is a work of fiction based on actual dialogues with schizophrenic patients, diabolically "sane" psychotherapists, and well-meaning yet unerringly destructive social workers. It chronicles the descent of an eccentric, sardonic, and witty psychiatrist into what appears to be a state of complete madness. Written in an evocative, lyrical prose style, the tale achieves a magical life of its own as the narrative twists, turns, and accelerates along with the doctor's free fall into the self. The novel demonstrates how ideation may be surrealistically transformed into a broken-language delirium that, despite its strangeness, remains eerily accessible.

Inspired by the author's work as a client advocate in the New York City mental health system, the book portrays a milieu in which the road to hell is paved with psychiatric good intentions.

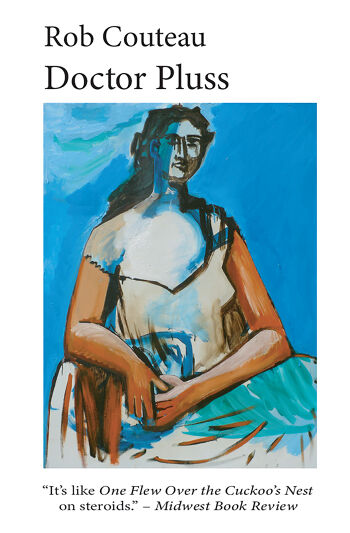

Doctor Pluss & Collected Poems by Rob Couteau

Review by Jim Feast

Reading Doctor Pluss, Rob Couteau’s intense, dramatic story of a psychologist who works at the Walt Whitman Asylum for Adults, one might think, especially since there is no authorial information given on the book, that Couteau is a psychiatrist of some sort. How else could he write with such assurance about this milieu?

However, turning to his book of essays, poems, reviews, and interviews, Collected Couteau, though it, too, contains no authorial information, one begins to see that he is a well-informed layman, who has thought deeply about psychological issues. Not only has he thought, but he has also forged a coherent philosophy through both the direct study of the subject and a close reading of literature.

Part of his philosophy is revealed in the interpretation of schizophrenia in a review of a book by John Perry. He notes that “Perry’s work in traditional psychiatric settings led him to conclude that those in the thrall of an acute psychotic episode are rarely listened to or met on the level of their visionary state of consciousness.” If care providers paid heed to what the patients were trying to show in their symptoms and musings, they would often find that, “forced to live an emotionally impoverished life, the psyche had reacted by provoking a transformation in the form of a ‘compensating’ psychosis, during which a drama in depth was enacted, forcing the initiate to undergo certain developmental processes.”

Couteau quotes Perry concerning this state: “The individual [patient] finds himself living in a psychic modality quite different from his surroundings. He is immersed in a myth world.” This modality may seem to be regressive, but it is far from unfruitful. “Although the [myth] imagery is of a general, archetypal nature,” writes Couteau, “it also symbolizes the key issues of the individual undergoing the crisis. Therefore, once lived through on this mythic plane, and once the process of withdrawal nears its end, the images must be linked to specific problems of daily life.” This leads, in the best cases, to a healing whereby the patient is now able to face and cope with problems that caused the flight into illness.

Perry’s work is not that well known, but readers may be more familiar with the once celebrated theories of R. D. Laing. While not finding archetypes in his patients’ thoughts, Laing agreed with Perry in treating the schizophrenics’ attempts to communicate as valid efforts to reach out, and in finding that their psychological difficulties were often rooted in their untenable lives.

This is not to say that Couteau wholeheartedly endorses these ideas of Perry’s. That’s not the point. Rather, Dr. Pluss, the staff psychiatrist in the novel named after him, does. Instead of coldly and clinically assessing his schizophrenic patients (as dominant psychiatric norms dictate he should), Pluss befriends them, sharing his own passions, such as his love of modernist art, particularly of Paul Klee, in a workshop where the inmates learn to appreciate art as a form of therapy. Further, he listens carefully to them as they exhaustively recount their life views. He may criticize these patients’ sometimes outrageous ideas, but he takes them seriously.

The description on the back of the novel states that the book is “based on actual dialogues with schizophrenic patients,” something evident from the stories told to Pluss. With a fantasy akin to Freud’s famous Rat Man case, one woman thinks a ravenous cat lives in her midsection. That’s why she constantly has to eat. Otherwise, the beast, in its craving for food, will begin consuming her internal organs. (In Freud’s story, the patient imagines rats gnawing on his friends’ buttocks.)

The most significant patient is Jonah, who believes his own mental problems are so tremendously fascinating that, when he engages in a self-analysis (talking to himself), somehow the Viennese master himself comes back to life to eavesdrop. As Jonah tells Dr. Pluss: “And Freud listened to the analysis, glued to his television. He wouldn’t eat; he wouldn’t sleep; he wouldn’t anything.” Ironically enough, Jonah’s psychoanalysis simply consists of enumerating, without explaining, his own situation. “I’m a patient; this is a hospital. Why am I in a cage?” While this fantasy may not seem terrifically engaging, when not raving Jonah presents thoughtful and provocative comments on religion, other patients, and even on Dr. Pluss, who is himself undergoing a nervous breakdown.

Pluss had been a painter but gave up the arts to devote himself to helping people. Now, as he is increasingly enthralled by some of his patients’ mythic visions, he begins painting again. Using notes of his talks with schizophrenics, he recasts their ideas as art. He creates, for instance, a series of paintings on Jonah, who sometimes thinks of his mind as a clockwork. Pluss depicts “Jonah being cured of paranoia at the Bulova Watch Repair School and leaving behind his persecution complex in the grim milieu of the Bulova assembly line.”

Couteau has some misgivings about the sympathetic ear approach of Perry. This is suggested by the fact that Pluss goes beyond listening to his patients’ stories, gets caught up by them, and eventually seems to go a little mad himself when he quits the sanitarium and disappears. I say “seems” because, mirroring Pluss’s dissolution, the narrative strands of the book, which had been tightly wound in the first section that focused closely on Pluss, begin to unravel, with Jonah taking over much of the narrative and becoming a new focal point. This shift of gears can be a bit disorienting as the realism of the opening is partially abandoned, but it does give the reader a chance to see the schizophrenia developing as it gains hold of Pluss’s thought processes. Pluss is like the psychiatrist Dr. Dysart in Peter Shaffer’s play Equus, who begins to doubt his profession, since when a cure succeeded, it often converted a passionate, inspired, if addled person into a normal but dull zombie. Pluss is attracted by the crazed creativity of so many of his charges. Unlike Dysart, though, who confines his admiration to rueful ruminations, Pluss mimics his patients, becoming psychotic in the process.

I mentioned previously that Couteau obtained psychological knowledge not only from studying and from thinking about books on the mind but also by reading literature. Indeed, it is important to note that while Pluss took the ultimately dangerous path of learning from his patients, Couteau has deepened his insights by interviewing great writers, such as Ray Bradbury and Hubert Selby Jr.

These interviews are not simple Q&A’s but are interactions with a lot of give and take. The interview with Selby (done for Rain Taxi) delves deeply into spirituality and ethics. In a notable passage, Selby remarks, “What we seem to be taught, at least in the Western world, is that we’re born with a blank slate, and we have to learn how to get and get…. But no one ever seems to train us in methods of finding out that we already have within us all the things that are valuable: all the treasures. But it’s only in the process of giving them away, to somebody else, that we become aware of having them.”

This thought seems to follow up on insights brought to bear in Doctor Pluss. One reason for the immobilization of so many in psychiatric offices or institutions (according to Couteau and the Shaffer of Equus) is that conventional education does not provide tools for people to deal with stress or act in a humanitarian, giving manner, only instructing them on how to get ahead.

I can’t help, though, but note that Selby, like Couteau, suggests he has learned from unique individuals, pointing to none other than Evergreen Review’s own editor, Barney Rosset, for special commendation. In discussing his first novel, Last Exit to Brooklyn, which Rosset published, Selby engages in an interchange, beginning with Couteau’s question:

"Why was Last Exit allowed to be published in the United States in 1964, while Tropic of Cancer, which was a much less obscene book – by the classical definition – was banned until just a few years before this?"

Selby: I think because … it [Tropic] had been banned for many years. You could only smuggle it in and all that sort of stuff. So, it had a different resistance and a different procedure to go through.

Couteau: It had an already established weight, a history that it had to deal with.

Selby: Right. Yeah. And, of course, Barney Rosset took care of business and made it possible for a lot of things to happen.

It’s nice to see that old debts – Rosset’s discovery and championing of Selby’s work – are here being repaid, but this also brings me to a final thought on history. Some readers may find Couteau out of date, in that Laing and the antipsychiatry movement to which he belonged are not the household names they were in the 1960s, but they (as represented by Perry) seem to orient and spur the author’s fictional and nonfictional excursions. While some may say this current of psychology has been superseded, Couteau has a gone a long way toward showing that it still possesses validity and staying power. How else account for the intellectual freshness, richness, and potency of his novel and essays?

Doctor Pluss

Rob Couteau

Dominantstar LLC

Print: 978-0-9966888-6-4

$13.95

Ebook: 978-0-9966888-8-8

$ 9.99

Ordering: www.dominantstarpublications.com

Website: www.robcouteau.com

Distributor: Ingram

Rob Couteau describes Doctor Pluss as "...fiction based on actual dialogues with schizophrenic patients, diabolically 'sane' psychotherapists, and well-meaning yet unerringly destructive social workers. It chronicles the descent of an eccentric, sardonic, and witty psychiatrist into what appears to be a state of complete madness."

His intention to metaphorically and realistically portray and contrast the madness of psychiatric process as well as its patients is powerfully wrought in a story about patients "surviving this holocaust of forgetfulness." During this process, their identities and personalities are lost in the institutional morass of a center purported to excel in rehabilitation, but which actually contains many ethical and personal challenges to the new psychiatric resident at the Walt Whitman Asylum for Adults, Dr. Pluss.

It's a place of rage and despair, of ambiguity where hope and horror run close together, and daily gives Dr. Pluss pause for thought about his patients and his role in their lives: "In her own unwitting way, Pluss mused, Evelyn personified the dual aspects of the godhead: horror and joy; awe and fascination."

Novellas typically are hard-hitting but often artificially succinct in their brevity. Often, one is left wanting for more. The best of them (of which Doctor Pluss is one) excels in taking this succinctness to its most logical conclusion, creating slices of life which are narrow enough to receive full-bodied flavor as the plot and characters develop.

One does not wish for more in Doctor Pluss. It's complete unto itself, exceptionally well developed, and emotionally compelling, connecting metaphorical description with experiences that often challenge the traditional roles of doctor and patient, linking them in unexpected ways.

Each patient has their own special struggle with perceptions and illusions that influence reality. Rob Couteau's descriptions are often long and detailed, demanding a slower, more contemplative reading style than is usual in novels in general and novellas in particular. These long sentences are packed with description that grabs heart and mind: "It was tragically convenient to blame her uncontrollable obesity and fierce primal appetite upon this crazy cat of the fleshy sphinx, this lazy Egyptian feline entombed within, lost in a drifting, timeless time of metempsychosis and crocodile gods, of the loopy eye of the ankh – the cross with a teardrop on top – mystic symbol for who knows what. Into the loop one entered and never again returned, adrift with the sacred crocodiles and lost in a thick bed of reeds asway in a warm, mosquito breeze, the muddy Nile lapping you along to your mother’s teat which is the grand fan of the delta: lush black earth of Moses and Nefertiti and Alexander and Akhenaton, all had wet themselves in her deltoid lap – let me wash you clean with my dirty waters and raise your material soul to a vast glittering realm of death, death, death – great Egyptian fantasy that delivered us to Hades, where we left this paltry life of the living and gladly marched to the everlasting realm of the deceased."

Run-on sentence, or beautiful metaphor for a mental condition? Couteau is not afraid to push the literary boundaries of convention in pursuit of a different form of descriptive truth, bringing readers along in a rollicking ride through schizophrenic experience that ultimately questions the foundations of reality and perception from both sides of the therapist's couch.

His interpretations and descriptions of the schizophrenic experience are particularly astute, astonishing, and evocatively described.

When Pluss vanishes, a ripple of effects on doctors and patients alike threatens to change everything. A regression process takes place that questions both convention and traditional roles.

Readers who choose Doctor Pluss are in for a treat. It's like One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest on steroids: a thought-provoking examination of sanity, insanity, and the crossover process that leaves readers thinking long after this therapeutic slice of life is consumed.

Excerpts from the forthcoming review:

"Doctor Pluss is exceptionally well developed and emotionally compelling, connecting metaphorical description with experiences that often challenge the traditional roles of doctor and patient, linking them in unexpected ways … Couteau is not afraid to push the literary boundaries of convention in pursuit of a different form of descriptive truth, bringing readers along in a rollicking ride through schizophrenic experience that ultimately questions the foundations of reality and perception from both sides of the therapist's couch … His interpretations and descriptions of the schizophrenic experience are particularly astute, astonishing, and evocatively described … Readers who choose Doctor Pluss are in for a treat. It's like One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest on steroids: a thought-provoking examination of sanity, insanity, and the crossover process that leaves readers thinking long after this therapeutic slice of life is consumed."