Horus Blassingame travels from Albion to Deresthia for a business conference that will change his identity forever in A True Map of the City by J Guenther. The fictional setting of this twisted novel creates tangible discomfort on every page, and the tragic spiral of Horus from suspicious stranger to local legend makes for a quick and bizarre read.

As Horus attempts to navigate his surroundings in a foreign land, he encounters a colorful stream of characters, but it is difficult to determine help from harm in such a backwards place. Only a handful of people speak Anglic (English), and his unexpected presence in this highly regimented land causes quite the stir.

It doesn’t take long for Horus to encounter the authorities, and end up in jail, which is when this book kicks into high gear. The head of police, Pokska, gives him an old map upon his eventual release, one that seems impossible to decipher – a puzzle within a maze. Horus only wants to find his way back to the hotel, and attend his conference, but he is once again waylaid by a misunderstanding, and a sneaky prostitute, landing himself back in jail with an even more serious charge.

While readers initially see the unassuming Horus as a bumbling outsider trying to muddle through a weekend conference, there is far more to this character than meets the eye. When faced with injustice, imprisonment, torture or death, the humble protagonist evolves before readers’ eyes, breaking down his moral walls in the face of such confusion and absurdity. With blood on his hands, a razor in his pocket and few friends in the world, he decides to impersonate a police officer to find nonexistent answers, as the rest of the authorities search every corner of the country for him.

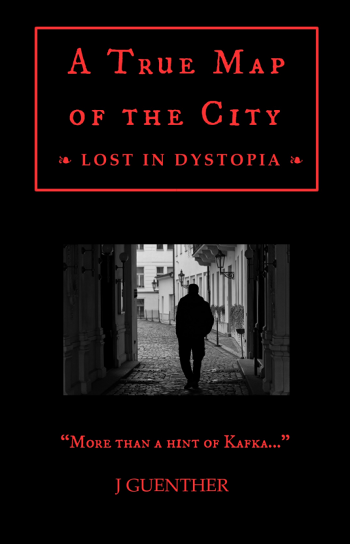

Peppered with deeply surreal moments, savage authorities, mysterious torture chambers, and a labyrinthine feel to every interaction, the only appropriate word for the tone of this novel is Kafkaesque. The constant feel of being lost in translation, and Horus’ inability to express his needs and desires clearly, creates a frustrating tension that is palpable throughout.

The plot is clever and delicately developed, the symbolism is richly layered, and every scene leaves readers asking head-scratching questions. The hyperbolic level of bureaucracy and hypocrisy occasionally comes across as satire, but also has the dark edge of Orwellian fiction – life being an impossible struggle controlled by unknowable powers. The unique language of Deresthok and the broken-Anglic style of dialogue is reminiscent of Anthony Burgess, as are the moments of violence and sociopathic self-reflection.

Creating such a surreal, vaguely impossible atmosphere in a novel is a challenging task, but Guenther plays masterfully with philosophy and language to achieve a singular mood. The stark, matter-of-fact narration and the intimacy of Horus’ inner monologue gives the prose a foreboding sense, while the flashes of humor and ridiculousness give the book an odd balance. Guenther fits a whole tangled tale into just over 100 pages, with few wasted words.

Capped off with a somewhat abrupt, and completely unexpected conclusion, A True Map of the City is a truly good read, and Guenther humbly proves himself as a literary descendant of Kafka himself.