To the world-class pantheon of memoirists like David Sedaris, Augusten Burroughs and Jonathan Ames, let us now add Don Cummings, who has single-handedly invented a new genre: the phallic memoir. Like all great personal essayists, the author mines his private torments—and tormented privates— transforming them, with wit, grace and weirdness, into a rivet- ing, original story of triumph and transcendence

Daring, funny, candid, tender, Bent But Not Broken reveals the paradoxical truth about manhood: our strength as men is our weakness, and vice versa. Don Cummings is a witty, insightful writer, and this book is a marvel.

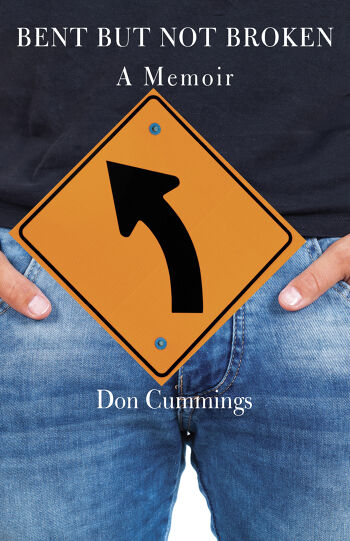

A playwright recounts his struggles with an embarrassing penis ailment in this debut memoir.

During the Great Recession, Cummings and his boyfriend of 16 years, Adam, moved to a small studio apartment in Queens. The author had noticed that his penis had begun to bend painfully to the right at an angle of 22 degrees, and he was becoming alarmed by it. A trip to a doctor confirmed that he was suffering from Peyronie’s disease, a genetic condition in which plaque builds up between the tissue layers of the penis. “Think of a piece of scotch tape on a balloon,” said his physician, searching for a suitable explanation. “When you blow up the balloon it bends in the direction of the tape because of the constriction. We need to break up that tape.” The treatment involved painful injections, not to mention exposing himself to a seemingly endless number of dispassionate medical professionals. The effect on his sex life—and the added stress for the already anxious playwright—put a strain on Cummings’ relationship with Adam and his flings with a number of other men. Even more, the situation caused the author to contemplate his long relationship with his suddenly endangered body part: what it meant to himself as a man and a mortal. Cummings’ skills as a writer are apparent from the beginning. His prose is effortlessly clever, finding the entertaining medium between lyricism and sass: “As I plowed through the field of life with its fecund and fallow seasons, I had at least had this decent tuber to hold on to. But blight was setting in, famine most likely soon to follow. Death felt more real. I was concerned that depression would take me over. It did—but not for long.” The frankness with which he discusses his problem, the treatment, and his sex life makes for an oddly shocking book—one rarely reads quite so much about penises, as central as they often are to literature. He manages to demystify and destigmatize Peyronie’s, which though obscure is not completely uncommon. More than that, he makes the most of an undignified opportunity to examine his own masculinity.

A blunt medical account that explores surprising terrain.

Bent But Not Broken is a hilarious and deeply moving memoir about a penis and its owner. But more than that it’s about the nature of love, the flux of relationships, and how bodies betray us all. Cummings is a stunning writer and excellent travel guide for this journey through his life.

“In Bent But Not Broken, Cummings has invited readers into his life, and the result for many will be a feeling of knowing this man well. Very well. It is a relationship with a storyteller that is entirely worth experiencing.”

Don Cummings begins Bent But Not Broken with a quotation by “Confucius, and others”: “The green reed which bends in the wind is stronger than the mighty oak which breaks in a storm.” This thought is intended, the reader may suppose, as a message of comfort to those who suffer, as Cummings does, from Peyronie’s disease.

Cummings, an author, playwright, and performer, has written a memoir that is also a manifesto, a missive of support, and a fearless monologue. The word “unflinching” only does partial justice to the courage of Cummings’ account of his life.

Indeed, the tone of Cummings’ book is that of a conversation with a close friend whom the narrator trusts enough to tell the most intimate details. Despite the realities of the editing process, if readers were informed that Cummings held back anything, most might react with substantial surprise. This is not the kind of history that leaves much to the imagination.

Cummings is of course the protagonist of his story, but his penis is an ever-present and often problematic sidekick. Several of the themes of this memoir are almost like secondary characters. The ravages of aging appear as a recurring subject, as do questions of fidelity, family, and self-awareness.

Cummings gets right into the medical condition that inspired the writing of his memoir. The first page of Bent But Not Broken informs readers that painful erections and painful sex with Adam, Cummings’ long-term boyfriend, were the first clues for Cummings that something might be seriously wrong.

Cummings is honest, sometimes brutally so, in describing his relationship with Adam. When he tells Adam of his concern about his penis, Cummings describes Adam’s response: “He smiled, slightly supportively, somewhat derisively, as he always did when presented with any frailty, especially my frailties . . .”

Cummings is no less forthcoming when describing his own foibles: “I like people who don’t care too much about me at first glance. I’m used to it. But I also hate it.”

Cummings’ search for a cure to the disease that is causing his penis to bend leads him to a doctor whose name keeps showing up online. Cummings describes, in often painful detail, the treatments. There are a lot of needles and bleeding involved, along with hours spent wearing a penis stretcher, repeated curvature assessments, and encounters with less-than-compassionate medical personnel.

In the midst of recounting his entirely understandable fear and anguish, Cummings shares moments of sublime wit. Speaking of the fibrous material that is among the causes of Peyronie’s, Cummings tells Adam, “I’ve named my scar tissue Roberta Plaque.” After a treatment, Cummings wonders if he’s being given a placebo by a “bunch of cock quacks.” It is challenging to not laugh aloud at the subtitle of one of his chapters: Taint Good.

Cummings alternates his search for relief from Peyronie’s with flashbacks to his childhood, college years, early adulthood, and past relationships. He unsparingly recounts ugly arguments with Adam, the frequent drinking of too much wine, the death of Adam’s father, and a truly terrifying episode in which he is drugged by an attractive man in a gay bar and is kidnapped to a sketchy restaurant in the Bronx, where the man disappears with Cummings’ credit and debit cards.

Cummings also shares the positive aspects of his relationship with Adam, saying that the good times, “took up more hours than our troubled minutes.” Though they come perilously close to breaking up for good, their relationship is ultimately saved, and they are now married.

In the end, the treatments, or perhaps, as Cummings observes, time taking care of everything, result in his penis getting better. The final chapter of Bent But Not Broken(subtitled Members Only) offers Cummings’ thoughts on dealing with Peyronie’s, with the proviso that he is “one person who went on one journey.” The last words of the book are realistic and encouraging for sufferers: “You will have your hopeless, angry, sad and frustrating days. Try to remain positive. No one ever died from Peyronie’s disease.”

Throughout this compelling memoir, there are universal truths among the specifics of Cummings’ life and his battle with a specific disease. As he observes of losing the pervasive sexual attraction he inspired in his youth, “age will age you,” words which will come as no surprise to anyone who is old enough to run for president. And readers who have ever been involved with—well, anyone—will perhaps find themselves nodding at his succinctly and poetically expressed: “Every relationship is its own torture rack.”

In Bent But Not Broken, Cummings has invited readers into his life, and the result for many will be a feeling of knowing this man well. Very well. It is a relationship with a storyteller that is entirely worth experiencing.

And if it might be considered glib, or in questionable taste, to point out that it is not necessary to have a bent penis, or a penis at all, to relate to Cummings’ fears, hopes, and struggles, it might also be just the kind of observation Cummings himself would enjoy making.

Like his penis, Cummings gets bent out of shape, and not only on account of his condition: also just by being human, a man, a gay man who wants what he wants, as most of us do: love, intimacy, sex, money, fame, and sex. Cummings can’t help but be funny, but he also can’t stop being honest, and his writing achieves real poignancy that will grab you by the heart and pen- etrate deep into your soul, if you’re the soulful type. If not, your mind, and definitely your memory. It’s an unforgettable, beauti- ful book.

From the moment he began seeing doctors, former actor and current storyteller Don Cummings understood his medical team. “They had two goals,” recalls Cummings, who many might remember from his time playing the gay waiter on Dharma & Greg. “The first was to diagnose whether or not I had Peyronie’s disease. They get you erect by injecting your penis with a drug and handing you pornography — old-timey, a magazine. They do, sweetly, ask you whether you want the gay or the straight porn.”

Once hard, the medical professionals, “cream up your penis and take an ultrasound, looking for plaque. If they find plaque, well, you have Peyronie’s disease,” he explains.

Then goal two: treatment. “In my case… it was Verapamil [in] saline injections. This has the effect of trying to turn the stubborn plaque from something like cheddar into Swiss.” But when first diagnosed by ultrasound, “I started to cry and told him how difficult sex had become.”

Today, Cummings is cured, and with Bent But Not Broken, he’s offering the first memoir about Peyronie’s disease, a disfiguring but usually treatable penile condition that afflicts 5 percent of men.

How did he cope in a world hyper-focused on dicks? He “escaped into wine and weed. I was not going to a psychotherapist at the time. That came later, once the depression and general hatred-for-living set in …. But I did not maintain my self-esteem around my penis. I was floored. I was told that I had a mild case of Peyronie’s disease. But I came in early for treatment and my guess is that I was not fully presenting yet. My doctor told me, ‘Most gay men come in sooner than straight men since they are more identified with their penises.’”

Inital treatments went well, “but then my penis got so much worse, bending, shrinking, constricting. There were days… I would look at the knives in the kitchen and I would think, One quick swipe across this deformed thing, and this bullshit will be over.”

He says, “to have an average penis that was not only shrinking to below average, but also, to curving into horrible shapes and nonfunctioning? What did this mean? What had I become?”

Eventually, Cummings “figured if I didn’t get into some sort of acceptance about the different routes my fate could take me, I would end up in enormous psychological trouble. Luckily, after six extra treatments and using the penis stretcher and being diligent, my penis did get much better. But it was a crapshoot and I have to say, I did not do it with any kind of grace.”

He didn’t plan to reveal all this in the memoir, but “with trepidation I went deeper… Once I got going I loved writing about my sex life, my feelings about sex, my problematic love life, and of course, my penis. We all have a sex life and we all have trouble. I’ve had a lot of sex. This should just be normal, to share these things with ease.”

Cummings’s husband was “very supportive” of the revealing book. “Adam was certainly wary of having our sex life out there… mostly because he’s a bottom. But I never understood any of his embarrassment about being a bottom.”

Today, the happily married Cummings’s book (dubbed a “phallic memoir” by Permanent Midnight author Jerry Stahl) joins the ranks of other great gay medical memoirs (think Augusten Burroughs’s).

Cummings is creating a space for people to come forward at his events, via social media, and even in the online support group he runs. “I’m happy to be ‘The Peyronie’s guy,’ since I am on the other side of it,” Cummings says.

“Had it turned out that my sex life as a top had ended, I would have accepted that.... I am not religious, but I do know I am not this body. How can I be? All these allergies and stomach problems and cancers and everything else we all have, health-wise? If I ever have a tombstone, and I won’t have one, but if I ever did, it would read, ‘My sinuses have never felt better.’”

--Actor and playright Don Cummings balances brutal honesty with humor in his new memoir about dealing with Peyronie’s disease as a gay man, Bent But Not Broken.

Sometimes it takes the licensing and advertising of a treatment to get patients to seek help, even for a medical problem that is often painful and psychologically devastating.

Such is the case with Peyronie’s disease, a scarring and bending or curving of the penis that can make sexual intercourse difficult or impossible for both straight and gay men. It most often afflicts middle-aged men, usually the result of an injury that may not have been noticed. Injury can occur during a sports activity, accident or vigorous sex when the erect penis is bent or pounded against bone.

In repairing the damage, the body creates plaques of scar tissue under the skin of the penis, causing it to bend or curve abnormally or become indented when erect. Before the end of 2014, when the Food and Drug Administration approved an injectable drug called Xiaflex, there was no approved treatment for Peyronie’s. Xiaflex contains an enzyme, collagenase, that in four cycles of treatment is injected directly into the plaque to destroy it and reduce the curvature.

One off-label remedy — multiple injections into the penile plaque of the blood pressure drug verapamil — is said to work in up to 40 percent of cases, though this has not been proved in a controlled trial.

One happy beneficiary of verapamil, Don Cummings, a 56-year-old playwright living in Los Angeles, has written a memoir about his experience, “Bent But Not Broken,” in hopes of encouraging other men similarly afflicted to seek professional help, especially now that Xiaflex is available.

“I know that men don’t talk about this, and I wanted other guys know they can get better,” Mr. Cummings said when I asked why he wrote such a revealing book. “I’m back to 95 percent of what was normal for me before Peyronie’s.”

Researchers estimate that anywhere from 1 percent to 23 percent of men between the ages of 40 and 70 are affected, although the actual number may be higher given that embarrassment keeps many men from seeing medical help. More than three-fourths of those affected are depressed and stressed by the problem.

“For the most part, men suffer in silence,” Dr. Jesse N. Mills, director of the Men’s Clinic at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in an interview. Given his urological specialty, Dr. Mills said he sees about 20 new patients a week with Peyronie’s, many of whom seek help after seeing ads for Xiaflex online.

“I don’t think the incidence has changed in the last 500 years, but more men are realizing there may be an effective treatment, though we still lack a celebrity patient who will do for Peyronie’s what Bob Dole did for erectile dysfunction,” the urologist said.

The penis consists of three tubes: the hollow urethra that carries urine and semen, and two soft, spongy tubes called the corpora cavernosa that fill with blood to stiffen the penis in an erection. All three are encased in a tough, fibrous sheath called the tunica albuginea that, when plaque forms, makes the sheath less flexible. Depending on the location of the plaque (in 70 percent of cases, it forms on the top side of the penis), it can cause the penis to bend up, down or to the side when it stiffens. Sometimes plaque forms around the penis, creating a narrow band like the neck of a bottle.

Heredity and certain connective tissue disorders like Dupuytren’s contractures increase the risk of developing Peyronie’s. Elevated blood sugar, smoking and pelvic trauma also increase the risk. The disease can develop gradually or come on suddenly. It occurs in two phases: acute and chronic. The acute phase, which often causes painful erections, lasts for six to 18 months, during which plaque forms and deformity of the erect penis worsens. In the chronic phase, the pain ends, the plaque stops growing and the deformity stabilizes.

Mr. Cummings’s doctor told him it was good that he came for treatment early, before the plaque became calcified and harder to treat. As he described it, the many injections of verapamil put holes in the plaque, “changing it from Cheddar to Swiss” and making the penis more flexible. He also spent hours a day stretching his penis with a traction device called Andropenis, an F.D.A.-approved penile extender.

This and similar devices can help lengthen a penis shortened by Peyronie’s and foster straighter remodeling as the plaque is replaced with healthy collagen.

“Xiaflex is not a miracle drug,” Dr. Mills said. “The trial that led to F.D.A. approval saw a 35 percent improvement in curvature, although we’re seeing about a 50 percent decrease. I tell patients ‘You’re never going to get back the penis you had, but you can get a functional penis,’ which is what most men want.” Only rarely does the problem correct itself without treatment.

Severe cases that don’t respond adequately to injections may be treated surgically, an option usually reserved for men with disabling deformities that make sexual activity difficult. Surgery is not done until the plaque and curvature have stabilized. Options include shortening the side of the penis opposite the curve or extending the curved side by filling in with a graft, a more challenging approach.

Some men with Peyronie’s disease who also have erectile dysfunction may be fitted with an inflatable pump or malleable silicone rods that straighten the penis and make it stiff enough for penetration.

As with all sexual problems, it helps tremendously to have an understanding and patient partner. Mr. Cummings said he was fortunate to have been in a loving 16-year relationship with his boyfriend, Adam, when Peyronie’s surfaced. Though the sailing wasn’t always smooth, he and Adam married as he neared the end of treatment.

Mr. Cummings said several women have told him that their husbands have the problem but won’t do anything about it. “Some doctors tell guys that there’s nothing that can be done about this. Men should know there is help out there — this is not something to be ashamed of,” he said.

Dr. Mills emphasized that although there is still no sure cure for Peyronie’s disease, therapy often lessens the problem. “Xiaflex is the best treatment we have, and it got only a B rating from the American Urological Association,” he said.

Although insurance coverage has long been hard to come by, most health insurers, including Medicare, now cover Xiaflex treatment for men with curvatures greater than 30 degrees. If your insurer denies coverage for Peyronie’s treatment, especially if the disease impairs sexual function, ask your doctor to file an appeal.

This Week in Sex is a summary of news and research related to sexual behavior, sexuality education, contraception, STIs, and more.

Peyronie’s Disease: When the Erect Penis Is a Source of Pain

Pain during sex does happen to people with penises. But we rarely talk about it. Discussions about painful sex usually center around vaginal discomfort or dryness, or advice on how to make anal sex more comfortable. For the most part, we assume that the person inserting Tab A into Slot B is having a good time.

Don Cummings, a Los Angeles-based playwright and author, knows from personal experience that this isn’t always the case. In his forthcoming memoir to be released March 15, Bent But Not Broken,Cummings opens up about his struggle with Peyronie’s disease. It’s a condition in which scar tissue or plaque can cause bent, painful erections. The scar tissue puts pressure on the inner layers of the penis, causing it to curve or indent when it gets hard. The condition, which occurs most often in middle-aged men, can come on suddenly or develop over time. Though its exact cause is unknown, it’s believed to be the result of an injury—be it rough sex, an awkward position, or a sports accident.

Cummings talked to Rewire.News by phone about his seven-year year struggle with Peyronie’s. He believes that he is genetically predisposed to it because his grandfather had a related condition, but he doesn’t know exactly what brought on the disease. He noted that he was catheterized (a medical procedure in which a small tube is threaded through the urethra to the bladder to allow urine to drain) and that some people are injured during this procedure. It’s also possible his condition may be the result of a series of small injuries during sex that he didn’t notice at the time.

But he was lucky. He had heard about Peyronie’s before he was diagnosed and had a pretty good idea of what was going on when he first went to the doctor. An ultrasound confirmed the diagnosis, and he started treatment early. That was important because the longer Peyronie’s goes untreated, the more scar tissue can harden.

He received injections of verapimal, a blood-pressure medicine, directly into the scar tissue to break it up. Cummings described the procedure as an attempt to turn “Cheddar into Swiss.” Off-label verapamil was the one of the only medications available until 2014, when the FDA approved Xiaflex, an injectable drug that contains an enzyme that destroys the scar tissue.

Along with the injections every other week, Cummings did four to six hours of penis traction each day using a device designed to slowly stretch and straighten the penis. Think of the scar tissue as a rubber band that keeps contracting. It has to be frequently stretched, so the penis can get back to its original length (or close to it). Neither of the treatments hurt, but the traction made Cummings pretty much immobile (“lots of reading in bed”).

And there was pain, especially during the first years after his diagnosis. It hurt the most when he had an erection. But even when he didn’t, he would get twinges and feelings that something just wasn’t right.

For the book, he decided to talk more about the emotional pain that came with having a dysfunctional penis and the strain that it put on his relationship with his now-husband Adam.

“Like many men, I got very depressed. In the chronic stage, you don’t know how you’re going to end up. I felt very out of control. I could have ended up completely sexually nonfunctioning. I was in a bad space and it colored my life,” he said. At 56, he’s one of the younger Baby Boomers; he went on to explain that men of his generation put a lot of stock in their penises. “You were taught that it was this very special thing, that it had a lot of pleasure, and a lot of power, and a lot of importance. If that goes wrong, you can just go into depression and shame.”

No surprise, then, that many men tie self-worth to their penises. “Guys, straight, gay, or otherwise, are kind of penis-obsessed,” he said. No surprise then that they don’t want to talk about penis troubles and may avoid seeking help. Cummings hopes that his book can start to change that.