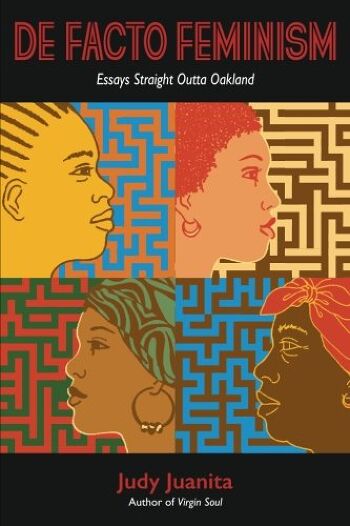

The essays in this collection from poet and novelist Juanita (Virgin Soul) provide a dynamic and illuminating take on a distinct subset of feminism nurtured by Oakland, Calif.’s community, as well as the story of Juanita’s coming of age as an artist. She provides vivid glimpses into her childhood in the 1950s in East Oakland and describes becoming aware of the “high status of light skin and non kinky hair,” along with her experiences in the Black Panther Party while attending S.F. State University in the 1960s and how it all came to inform her identity as a black woman activist. Juanita presents a slew of cultural factors including TV and the Beatles as contributing to the black revolution, the black arts movement, and the rise of black women’s feminism as a distinctive movement. She uses the term “de facto feminist” to describe herself, and black women in general: “De facto feminism is like de facto segregation, which remains the way our nation is organized. De facto segregation is the practical reality of separation of members of different races, not by law... but in practice by various social and economic factors.” Personal reminiscences (“We were the first family on the block to visit Disneyland”) mixed with pop culture details (“At a Beatles concert in Plymouth, Great Britain, in November 1963, police used high-pressure hoses on screaming fans, a show of authority that matched the hosing of demonstrators in Birmingham six months earlier”) create a rhythmic and unforgettable portrait of an artist and activist coming of age. (BookLife)

The essays in this collection from poet and novelist Juanita (Virgin Soul) provide a dynamic and illuminating take on a distinct subset of feminism nurtured by Oakland, Calif.’s community, as well as the story of Juanita’s coming of age as an artist. She provides vivid glimpses into her childhood in the 1950s in East Oakland and describes becoming aware of the “high status of light skin and non kinky hair,” along with her experiences in the Black Panther Party while attending S.F. State University in the 1960s and how it all came to inform her identity as a black woman activist. Juanita presents a slew of cultural factors including TV and the Beatles as contributing to the black revolution, the black arts movement, and the rise of black women’s feminism as a distinctive movement. She uses the term “de facto feminist” to describe herself, and black women in general: “De facto feminism is like de facto segregation, which remains the way our nation is organized. De facto segregation is the practical reality of separation of members of different races, not by law... but in practice by various social and economic factors.” Personal reminiscences (“We were the first family on the block to visit Disneyland”) mixed with pop culture details (“At a Beatles concert in Plymouth, Great Britain, in November 1963, police used high-pressure hoses on screaming fans, a show of authority that matched the hosing of demonstrators in Birmingham six months earlier”) create a rhythmic and unforgettable portrait of an artist and activist coming of age. (BookLife)

This extraordinary set of autobiographical essays gives insight into a black woman’s life in the arts: everything from joining the Black Panthers to avoiding African-American chick lit.

Juanita (Virgin Soul, 2013) grew up in Oakland, California, in the 1950s. She remembers a “goody-goody” childhood of reading, spelling bees, and chores. America at the time was “a Jell-O & white bread land of perfection and gleaming surfaces,” she notes in her essay “White Out”; the only blacks on screen played mammies and maids. She joined the Black Panthers at San Francisco State in 1966 and became a junior faculty member in its Black Studies department—the nation’s first. In perhaps the most powerful piece in the collection, “The Gun as Ultimate Performance Poem,” written after the death of Trayvon Martin, Juanita sensitively discusses the split in the Black Panthers over carrying guns. She liked guns’ symbolic associations and even kept one in her purse while working at a post office. But she now recognizes the disastrous consequences of romanticizing a weapon: “It was Art. It was Metaphor. It was loaded with meaning and death.” In another standout, “The N-word,” she boldly explores the disparate contexts in which the epithet appears: in August Wilson’s play Fences, in comedy routines, and intimately between friends. “It’s not problem or solution; it’s an indication,” she concludes. The title essay contends that black women are de facto feminists because they’re so often reduced to single parenting in poverty. Elsewhere, she discusses relationships between black men and women, recalls rediscovering poetry as a divorcée with an 8-year-old son in New Jersey (“Tough Luck,” which includes her own poems), remembers a time spent cleaning condos, and remarks that Terry McMillan has ensured that a “black female writer not writing chick lit has an uphill challenge.”

The author refers to herself as “an observational ironist,” and her incisive comments on black life’s contradictions make this essay collection a winner.

“Terminology makes for binary thinking dilemmas” (162)

“In protest movements, as in wars, the people on the bottom don’t write history” (156)

I always felt that one of the reasons the Occupy Wall Street 99% movement (of 2011/12) was doomed to failure, aside from hostile external forces like the police, the corporate media, and the ostensibly non-political real estate market, was because there was a wall of misunderstanding between those who set up the occupy camps (where everyone gets 5 minutes to speak at a microphone), and those fighting more through the formal mediation of art, writing, or recorded music. Both were needed for the movement’s success, but some of the former, at their worst, declared that they were the true activists and accused the latter of wanting to be “leaders” or “spokesmen”—or too individual while the latter, often on the defensive, would respond by accusing the former of making no room for the contemplative mode or the more inwardly-driven introvert. It didn’t help matters that many of the whites whose voices tended to dominate this “leaderless” movement were also not taking seriously the concerns expressed of the black women who showed up at rallies with signs that said “blacks have always been the 99%.”

By contrast, in my experience, I’ve found that the most vital, engaging, even potentially revolutionary, grassroots social arts and political scenes and movements are able to form bridges across specialized professions or segregated communities. For instance, the underground scenes that provided me shelter and community in Philadelphia (in the 80s) and to a lesser extent in Oakland (during the 00s), at their best, found the creative spark that fueled them by crossing lines between “town” and “gown” (the streets and college), between “doers” and “thinkers,” or a more ‘blue collar’ (punk and hip hop) and white collar ethos, and not merely on a fashion level; they even helped bridge the gap (if not smash the wall) between whites and blacks (graffiti was an especially important bridge in the 80s). Sure, there were limits to this “unity in diversity approach” (since many of these scenes were youth scenes, they still struggled with ageism, even if it was a defensive ageism), but there was a recognition that the thinker and doer, the artist and the activist, need each other if there’s any hope that the alternative economy and culture we were creating was to be sustainable, something more than another transient flash in the plan, and generally, in my experience, the women in these scenes understood this—and served as voices, and forces, of unity—more than the men.

Ex-Black Panther, and “lone wolf,” Judy Juanita’s new De Facto Feminism: Essays Straight Outta Oakland (2016) sheds many insights into these dynamics in ways that can be useful for any future artists and activists who wish to work together to form a movement that may topple the patriarchal, plutocratic, racist imperialism that dominates American reality in an era of global capitalism. She understands the psychology in which “activists, oft called anarchistic, despise artists who don’t overtly join them.” (108) Some feel it’s an unequal trade, that somehow the artists aren’t giving back what they’re receiving. In any event, I’ve heard many activists scold the very people they’re trying to recruit, or seduce, “you’re acting too much like an individualist, a bourgeois individualist.” But it’s one thing for a white (often male) ideological anti-individualist to scold another white male for being an individualist, but given life in a country where whites (especially men) have been afforded the full-rights of individualism compared to black men and women, it’s quite another for an ideological anti-individualist to criticize a black woman, especially when it may be as an individual that a woman is able to create alliances across factions.

In De Facto Feminism, Judy Juanita celebrates the working class black individualist…by showing the (oft-unheralded) ways they help build community, not through theoretical imperative, but simply in order to survive. The women Juanita celebrates transcend the false “binary thinking dilemmas” (between artist and activist, and between individualist and collectivist) to engage in an artistic activism, and an altruism that need not be self-abnegating that occupies a fertile, proliferative, place where selfishness and altruism, individualism and community activism can unite. For sometimes the reason why one doesn’t “fit in” to one social scene is the same reason you can get along with more people from other social scenes.

For Juanita, this has been a life-long struggle, “an act of self-creation spanning 4 decades,” and De Facto Feminism is a record of her findings that can be useful for current and future generations of artists and activists in their struggles.

During her time with the Black Panthers, which in hindsight she calls her phase of “naively determined black womanhood,” Juanita had been an idealistic anti-individualist collectivist (In “Black Womanhood,” an essay Juanita wrote at the age of 20 for the Black Panther Newspaper, she writes that the struggle requires “her strength, not her will, her leadership, her domination, but her strength”). But, it must not be forgotten that Juanita, even as a young woman, was not just a Black Panther, but also part of the Black Arts Movement (BAM which may not be as well known to the general reader)[1]:

“As student activists at SF State, the Black Student Union fought to bring Jones (Baraka), Lee (Mudhubuti) and Sanchez onto Campus. We formed the Black Arts and Culture Troupe and toured community centers throughout the Bay Area with poetry, dance and agit-prop plays. We enacted ideas we were hearing on soap-boxes about black power, black consciousness, and black beauty. We staged mock conflagrations like ones that were taking place in urban cities. We were empowering ourselves, our communities and getting academic credit. A natural progression was community activism.” (110)

When she joined the Black Panthers, she was drawn to the alliance between artists and activists, but witnessed, during an era of “shattering community,” a growing split between the two groups: “to look at the BAM and its relation to the BPP renders a vision of the poets and the dramatists standing in counterpoint.” Ultimately, however, “the activists upstaged the artist/intellectuals. I had immense sympathy for the second group, but pitied them (pitied their women more. How much subservience would soothe a wounded ego?)” (107)

Despite the chauvinism she found in the BAM more than in the BPP, and the factionalism and her torn allegiances, Juanita appreciated what the BPP and Black Arts Movement had in common, and celebrates this legacy:

“The BPP was appropriating the oppressors’ language, and using it to shatter oppression. That new use of language, in the BPP and the BAM, was as powerful as any gun, and even more powerful because it aroused feeling and changed the terms of discourse between friends, enemies, lovers, generations and cultures. Being an agent of change meant I aroused deep feelings, affected discourse, found the powerful voices that I had heard in childhood, in church, in soul music, in the pulpit—in my own voice.” (111)

Juanita’s allegiance was both to art and to activism, and she didn’t want to be forced to choose, and as we see her mind go back and forth between the BPP and the BAM, weighing the advantages of each and trying to develop a new synthesis, we see her

ability to step back from the heated conflicts and tense divisiveness between the artists and activists to see the productive symbiosis: “Black music, musicians and dancers became ambassadors at large to the world But the airwaves and new media[2] amplified the beat, the dances, the Soul Train lines, the frizzy hair, the handshakes, the lingo (bro), now of which needed the Gun or its bullet because the BPP handled that task,” (113) and part of the reason the BPP was able to handle the task is because of what women like Judy Juanita (a.k.a. Judy Hart) provided.

As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of both the BAM and the BPP, the role of women in the Black Panther party (which was numerically mostly women) is still not emphasized enough in biopics like the recent PBS Vanguard of The Revolution, (2016), yet even in Seize The Time (1970), Bobby Seale wrote of the first women in the Black Panther’s power to educate and recruit new members to the party. Juanita, ex-editor-in-chief of the Black Panther newspaper, gives her own account of the importance of these young women as bringing together rival factions to create and sustain a larger, more rooted, movement. Certainly, Juanita and the other women were no passive recipients of edicts from Bobby, Huey, and Eldridge:

“Our gang of five affected policy and high-level decisions by virtue of our intense participation, outspokenness….we also formed liaisons and romantic relationships with brothers in the party. From the upper echelon to the lumpen proletariat, we lived, slept, ate and cooked with the BPP…. We were the initial link between the campus and the party. Three of us married ‘brothers in the struggle’ who also happened to be educated brothers. This is significant because our connections and intimacy (which some labeled promiscuity) connected brothers from the party with brothers from SF State. The BSU brothers like to talk about supplying the BPP with guns and money, but this bridge called my back supplied the people’s army with equal and greater provision.” (40)

This final point provides a great example of what the mature Juanita refers to as “De Facto Feminism.” In her title essay, she offers her own definition of “de facto feminism” by contrasting it with the 20th century feminism she experienced:

20th Century feminism is “defensive, lean-in elite, scarce, historical, white-ish, precious, theoretical, lawful, contempt for men but not their $$$.” De-facto feminism is “offensive, classless, proliferative, a historical, black and then some, inside/outside the law, do you with/without men” (146). This contrast does not get tangled up in the academic debates between the “difference” and “sameness” feminists, but is a celebration of the practical de facto feminists who “stand between peace and war everyday in…the Gaza Strips of the US” in the absence of being able to change the laws.

Although she claims de facto feminism is “classless,” it’s clear that it’s working class as Juanita never loses sight of the economic dimensions to patriarchal sexism, especially when coupled with “the stigma that black people carry as pigment” that “forces them to be what others would term illegal, immoral but not impractical.” (151):

A whole class of workers constitutes women who braid hair, part of the underground economy in the black community. Overwhelmingly black and youthful, they work from home, a cadre of postmodern kitchen beauticians who make a way out of no way, to raise children, make money, be stylish and create community.” (150—emphasis added).

Her accounts of these various and varied women remind me of other women I’ve met in Oakland. When I read about “Shelly,” (152) I think of the amazing Phavia Kujichagulia (“She also had a disinclination to sell her body for a recording contract”). And when I read: “In New Jersey, I lived in a six-unit building with several foxy single mothers who attracted and “housed” members of the New York Giants football team during the season,” I am reminded of another book by an Oakland author released this year, ElTyna McCree’s Oh What A Ride!

Although, like Juanita, McCree was born in 1946, and ElTyna can certainly relate when Juanita writes “hands-on celibacy became my unspoken choice for years,” their two stories are very different. Eltyna grew up near Pittsburgh, PA, working for Allegheny Airlines while Juanita was editing The Black Panther.” A devout church-goer, McCree worked closely as Director of Convention Services, and was the official travel coordinator for the Church Of God In Christ COGIC, booking reservations for conferences and becoming ordained as a preacher. Fleeing from a destructive marriage back east, she (with the help of God) reinvents herself in Oakland running the Connections Unlimited travel agency for over 30 years—and running for School Board as a republican in a democratic city—all without a college degree--before gentrification cost her her shop. Reading Juanita’s book, I think of Eltyna’s quite different (but in some ways similar, minus the sex) services she provided for the Miami Dophins when they came to Oakland for the Super bowl:

“The one and only superbowl was being played at Stanford. The SF 49ers and the Miami Dolphins. We had our new hotel in Oakland, which was hosting the Dolphins. We were beyond excited. In those days I was so dressed up every day. I decided to walk up to the Hyatt just to check on everything. I arrived at the concierge desk. There were about 30 folk there all needing something. She was overwhelmed, I told her to take a break. I sat down. Well, that was Friday morning. I didn’t walk out of the Hyatt til Monday at 1 p.m. Some of the Dolphin players wanted their game tickets sold. The women needed babysitters, needed to have their hair and nails done. They wanted to do to San Francisco for dinner. I knew where to get every resource. Jim Cole’s sons and my goddaughter Ayoka (they went to Calif Prep school together) helped with kids activities. Hair and nails got done. I rented Lincoln Town Cars and we got coaches for their wives to dinner in San Fran and Sausalito. Local folk were asking for transportation to the game. I chartered a bus, got box lunches, and cases of champagne for the bus. I, Miss Fly, was wearing 14 karat gold nails and players wanted to buy them for their wives, or girlfriends. I got Ruby’s Gold Finger nails to come over to the hotel, an we sold those…Dolphin general manager Mr. Callahan andI remained friends for years. When I walked out of the hotel that day, I had profit of 4800.00 in cash. Through her ups and downs, Eltyna too may also join the legions of women Juanita celebrates as “walking talking political education classes who teach persistence when things don’t work out?” Ain’t she a de-facto feminist?

Juanita’s essay can also remind me of my own Italian grandmother who I know, alas, too little about, aside from her having to come to America as a mail order bride and, when her husband died young, leaving her with 8 children, used her social and business skills to, among other things, run a numbers racket, even though she was illiterate and I could barely understand her English. Juanita’s own great grand mother, an Okie from Muskogee, took books and magazines from the homes of rich white folks where she worked, and helped form that town’s first free colored library! (160)

All of the women Juanita celebrates in this essay, she boldly claims, “are far more feminist than the broadcast/weathercasters who’ve memorized feminist principles and theory from prep school through Ivy league. Juanita also nods to the women who founded #BlackLivesMatters when she writes, “a new wave of feminists instead might envision women of color setting policy and leading, being arbiters instead of being left behind,” (153) and I think of the #LaughingWhileBlack women scolded by a white woman on the Napa Valley Win Train (2015), and their unheralded contributions to the legal corporate economy when Juanita celebrates the book clubs that gave “mainstream publishing a shot in the arm.”

Reminding us that “in protest movements, as in wars, the people on the bottom don’t write history,” Juanita uses her literate skills throughout De Facto Feminism to speak of, to, and for, those de facto closer to “the bottom,” and asks “will it take 200 years for respect to come to those de facto feminists sitting on the bottom, squeezed into pink collar ghettos and brown security guard uniforms lined up at the minimum wage margins of this world?” (156)

Although Juanita expresses a justifiable disgust with “the white-ish, lean-in elite” characteristics that is the legacy of dominant 20th century (second-wave) feminism, her book does contain one instance that celebrates the de facto (rather than de jure) feminism of the white women. During her adolescence in 1964, during the period when Sly Stone wrote “The Swim,” and helped create a dance craze working closely with white topless dancer Carol Doda, Juanita writes of the powerful convergence that The Birth Control Bill and Beatles created for whites. As a teenage Juanita watches young white women starting to dance more with black women (even as their parents are leaving the neighborhood), she notices:

“All the prepubescent and adolescent white girls having orgasmic and orgiastic responses released a long suppressed sexuality from its Victorian, Southern, and Puritan constraints. As these women let it rip in that prolonged moment of free public expression, they freed up black women from whoredom, from bearing the brunt and hard edge of the white men’s sexuality. We were no longer the only culturally-sanctioned object of naughty or forbidden sex, of plantation promiscuity.” (33-4)

This is one instance where young white women—by liberating themselves—were able to do more to liberate black women than any of their paternalistic Moynihan-Report inflected proclamations could….or would. Juanita’s perspective on this time when de-segregation seemed promising through music and dance should be must reading for any historian of the swinging sixties sick of the Male Baby Boomer Rock Critic establishment’s version (Greil Marcus, et al) and, shows, the ways in which the more ostensibly “apolitical” music of the early 60s (the groundswell from the segregated R&B stations) had more power than 70s “profound” light rock whose rise paralleled the rise of white-ish feminism.

And, finally, she offers a powerful argument for why whites should care, and not just for “altruistic” (paternalistic) reasons, but yes, for selfish reasons. “Black people often serve as an early warning system for the American populace…for better and worse, the hardcore issues blacks face—guns, crime, poverty, failing schools—define the newest America.” (161). As the standard of living for most whites in America has been noticeably decreasing since the great crash of 2008 (although not as much as it is for blacks), Juanita reminds me a little of those women at the Occupy Rally with the “Blacks have always been the 99%” sign, as if to say “welcome to the club.”

+++++++++

I’m a woman. POW! Black. BAM! Outspoken. STOMP! Don’t fit in. OUCH! The lesson? Sometimes when one takes a stand one becomes a lone wolf, a neighborhood of one, a community of one to declare sovereignty for art, sexuality, spirituality, and say-so, an individual.” (7)[3]

De Facto Feminism, however, includes a much more varied range of writing than my essayistic explorations of two of its more publically-inflected threads may suggest to one who hasn’t read it. Even if you have no interest in the Panthers, or community activism, or in feminism, per se, there are many personally-inflected essays that focus on her life as a writer. It is not merely a series of essayistic arguments, but maintains “the feel of memoir” as these essays are the book is a loosely constructed chronology/autopbiographical journey. Eschewing the fictional mask of the “unreliable narrator” Geniece in her semi-autobiograpical Virgin Soul, the political and the personal come even closer in De Facto Feminism, as Juanita casts a retro-spective glance from which to build a present and future, without debilitating nostalgia.

Because Juanita published Virgin Soul (2013), in her late 60s, what people used to call one’s retirement years (when one could get away doing that), some may “see” her as a “late bloomer.” Yet, what Juanita was doing these years, was not merely honing her craft, but also exploring different social dynamics in which art circulates (as she explores the social interactions in the theatre world, the stand-up comedy world, and even the poetry world), and also digesting (if not exactly recoiling from) the extremely intense “baptism by fire” she experienced at age 20 in the Black Panthers as an agent of change. The years in between are hardly “lost years.” Juanita is able to make art out of stint as a maid in “Cleaning Other People’s Houses,” in addition to increasing her empathy for the working class women she champions. In a sense, the essay on Carolyn Rogers may be the most personal, as obviously Juanita can relate to a woman celebrated by the BAM, but later forgotten as she eschewed the “militant” posture which made it easier to get published during this time.

In these essays, Juanita emerges as a working class artist/intellectual (which our dominant culture tries to tell us is an oxymoron), and a working class teacher, one who is highly skeptical of the ready-made solutions, and the ridiculous gerrymandered specialized genres. She challenges the social nexus that too often determines the circulation of literary texts in our society, and yet emerges triumphant. As she speaks of the way she learned to become a novelist, by jumping from many social scenes and roles as artist/intellectual, I see a writer relentlessly measuring the inner world by the outer world, and vice versa.

Although she doesn’t mention much about her role as teacher in this book, many of the essays can be useful in a creative writing class, in the sense that they show the many different social roles a novelist may play in order to enhance one’s long-term commitment to her art. If people say your story telling it not funny enough, why not show up at stand-up comedy night, and try that out….with no illusions you’ll become a famous stand-up comic, but it can help your writing. And seek out writers groups! When she writes about some golden lessons she learned about herself and writing (in A Playwright-In-Progress), one insight is “I learn through making big, fat mistakes vs. reading/perfecting it in my mind.”(73) I, for one, can relate to that, and I know many others who can: yes, sometimes we publish precisely in order to make a mistake public, as if that is the only way to move beyond it. Part of why Juanita’s such a great teacher is because she can relate to the student going through that, or the student who doesn’t know which genre they should put their primary emphasis: poetry, fiction, or plays…for in this specialized society, you must choose one, and for one like Juanita, that is not always an easy choice…(as if she, like Frank O’Hara, is more interested in that “grace to live as variously as possible”), but it precisely the life-long battle with that choice that makes Virgin Soul such a great novel, as this novel is conversant with so many other genres (drama, and poetry, and stand-up comedy, with Black Panther Newspaper agit-prop, as well as with the oft unheralded art of cleaning other people’s houses). This, in fact, is why Virgin Soul, through its art, has been able to help create community years after many other Panthers were jailed for the same thing. One doesn’t have to have read Virgin Soul to appreciate De Facto Feminism, but they certainly complement each other.

In another writer’s hand, such reflections may seem self-indulgent, but Juanita never loses sight of the light she’s shining for those unspoken for which her younger self may have been tempted to judge. She never loses sight of the collective struggle, and of the fact that some things must be kept secret, in offering brilliant advice for organizers: “Caucus as an intransitive verb meant your group agenda had to be strengthened privately and exhaustively to have maximum ”impact.” (111) Indeed, this is a book a 20, or 30, or even 50 year old, could not have written….

[1] Her essay is thus a perfect antidote to many academic essays about the Black Arts Movement (in which white writers often debate on “what happened to Le Roi?” “oh he hates us now”)

[2] I can’t resist noting that the new media 50 years later seems to designed to prevent exactly the things the old media amplified.

[3] Notice her use of artful puns. BAM is not just a Batman-and-Robinism, but the Black Arts Movement! (thus, POW could be Prisoner of War?)

[4] See also, 27. The Hotel California where coloreds couldn’t play, the Social Club where they did, and the integrated Oaks club”