As that anecdote suggests, Goggio’s story is at times tricky, and Brown, while writing with great love, admirably faces the complications. His thoughtful examination of them becomes gripping once Goggio, at the University of Toronto in the 1920s, begins not just lionizing Italian culture but the nation itself, under Mussolini. Brown’s thorough, revealing parsing of his grandfather’s extant writings and lectures illuminates Goggio, his era, and the truth that, in the early years of Italian Fascism, support was often mainstream. Goggio was well off the “train” by 1940 and continued, in his work, to strive to foster “a spirit of mutual respect and understanding between the native and foreign elements in the United States.” (He once pitched a film on this theme to D.W. Griffith.)

Brown draws on interviews he conducted as a student with Goggio in 1968, plus letters, Goggio’s writings, and much well-deployed research. The result is an insightful, compelling portrait, with revealing explorations of late 19th century Italian education, Boston urban planning, American hatmaking, Italian life in Toronto, and the quite-human reasons one might leave a professorship before a brother hits campus.

Takeaway: Loving, complex portrait of a 20th century Italian academic in North America.

Comparable Titles: Jerre Mangione’s La Storia, Franca Iacovetta’s Such Hardworking People.

Production grades

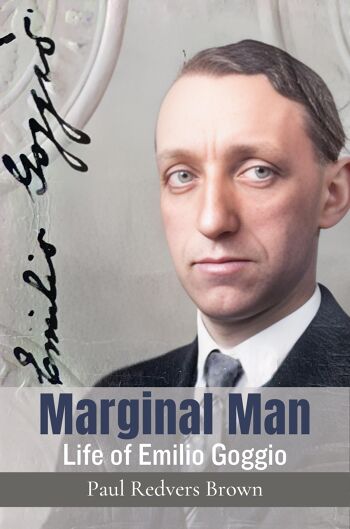

Cover: A-

Design and typography: A

Illustrations: A

Editing: A

Marketing copy: A

Brown’s biography chronicles the life of Emilio Goggio, an Italian American educator who dedicated his life to the preservation and promotion of Italian culture abroad.

In 1885, Emilio Goggio was born in Incisa Belbo, a small village in Piedmont, Italy, and grew up in the atmosphere of patriotic fervor that followed Italian unification, an experience that profoundly shaped his attachment to his idealized native country. Awash in rhapsodic nationalism, he was devastated when, at the age of 14, he was sent to Boston to be reunited with his father, Francesco, who had left Italy to start a hat-manufacturing business in the United States. Francesco had departed his home country the year his son was born, and Goggio didn’t know his father at all. The boy arrived speaking no English, but he was as intelligent as he was diligent; in 1906, at the age of 20, he was accepted into Harvard University. In 1917, Goggio earned a doctorate from Harvard, and he would go on to hold academic appointments at several universities, including the University of California at Berkeley and the University of Toronto, teaching the language and culture of Italy. Eventually, he determined that his core academic mission was “documenting the penetration of Italian influences in America” as well as in Canada, a passionate devotion movingly and lovingly captured by the author, his grandson. In fact, Goggio believed in his cause so deeply that he expanded it beyond a scholarly interest—he wanted to spearhead a nationwide increase in the enrollment in Italian studies programs and fashion a more favorable public opinion of Italian culture. To that end, he didn’t limit himself to publishing academic articles, also penning newspaper editorials and even cinematic screenplays. There was a dark side to Goggio’s ardent patriotism, however, as well as a naïveté—both evident in his admiration of Mussolini and in his support of his Fascist policies.

With impressive journalistic meticulousness, the author attempts to precisely define the nature of Goggio’s sometimes murky association with the Italian government, which certainly involved the dissemination of state-sponsored propaganda, for which he likely received monetary remuneration. In fact, Goggio was so successful at “spreading the gospel of Fascism” that he was knighted by the King of Italy. With admirable intelligence and clarity, Brown attempts to explain how such a morally decent and thoroughly intelligent man could become so attached to a politically nefarious movement: “Professor Goggio was predisposed to embrace the patriotic signals emitting from radio beacons in Italy. He was entranced by Mussolini’s showmanship, having been awakened to the powerful appeal of mass media himself. From his location in North America, ‘Italy’ was a combination of literary trope, nostalgic memories, and cultural iconography. Emilio’s Italy flourished in the landscape of his mind—the ethereal home of his self-esteem and identity.” The sole failing of the author’s thoughtful biography—one that’s unabashedly affectionate but appropriately critical as well—is that he dwells on the minute details of Goggio’s quotidian and professional life in an apparent attempt to achieve encyclopedic comprehensiveness. As a result, some sections read like a narrated curriculum vitae. Nonetheless, this is an intellectually engrossing work and a thrilling portal into tumultuous historical times.

A captivating blend of personal biography and world history.