The essays collected here offer illuminating explanations of her work and influences. However, it is the extended interview with Alan Bruton illuminating the artist’s thoughts on her own works and the eras in which they are created. Two recurring names throughout the book are John Cage and Steve Reich, composers whose pioneering use of space and time corresponded with the artist’s own ideas about physicality and the melding of sound and art. The artist states she was looking to “Create a sonic space that moves through the physical configuration, essentially directing and manipulating the gallery visitors' experience.”

While such immersive installation work can’t be fully captured in a book, Threads and Layers offers an excellent synthesis of text, photos, and reproductions, capturing the essences of this bold, resonant work while giving meaning and context to an artist’s life and ideas—and leaving readers with much to unpack, digest, and imagine. Highly recommended.

Takeaway: Thrilling survey of artist Sara Garden Armstrong’s career.

Comparable Titles: Alan Licht’s Sound Art Revisited, James Turrell: Lighting a Planet.

Production grades

Cover: A

Design and typography: A

Illustrations: A

Editing: A

Marketing copy: A

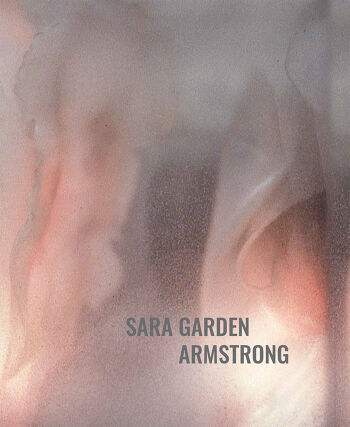

A volume of essays and photographs highlights the career of a multimedia artist whose works explore themes of movement, breath, and the relationship of humans to the environment. Beginning with the cover of the book, readers will be quickly immersed in the muted abstract sensuality that characterizes much of Sara Garden Armstrong’s art, whether in the form of paintings of dreamscapes superimposed with words and graphs or an amorphous sculpture casting shadows that “paint” the wall behind with dense layers of shapes. In his foreword to the volume, David Ebony, contributing editor of Art in America, calls Armstrong’s work “prescient and urgent,” asserting that she shares with Leonardo da Vinci a scientist’s “understanding and appreciation of Earth as an organism, corresponding quite closely to the human body.” Gail C. Andrews, former director of the Birmingham Museum of Art, who has known Armstrong through much of her 40-year career, praises the artist’s constant exploration and experimentation in terms of themes, techniques, and materials. Other essays elaborate on the investigative fearlessness of Armstrong’s creations, such as “The Process,” in which Daniel White defines the artist’s overall mission statement as “keep asking questions.” The book, edited by Gustafson, is well constructed for showcasing Armstrong’s life, vision, and body of work. Vivid images by various photographers depict myriad views of the artist’s paintings, sculptures, and books, presenting convincing proof of Jon Coffelt’s contention in an essay that “Armstrong’s work is alive. It poses and postures and sometimes breathes.” The volume’s pieces, written by artists, critics, and curators, are wide ranging and include dissections of Armstrong’s use of sound and movement in Dan R. Talley’s “Drawing Breath”; a revealing interview with the artist in Alan Bruton’s “Airplayers and Beyond”; and a history of the trailblazer’s studios in Alice Meriwether Bowsher’s “A Space To Call Home: A Place To Work.” Steffany Martz anchors the narrative with an exhaustive, illustrated chronology. The last page echoes the multidimensionality of Armstrong’s own work by offering QR codes that provide easy access to 18 videos that elaborate on her artistic approach. Both longtime fans of Armstrong and those who are new to her oeuvre will find much to appreciate here.

A comprehensive and illuminating examination of an influential experimental artist.