[Powerful prologue and other parts now streamlined, seeking a larger publisher:] The Ash Tree – a novel -- tells a timeless story of the romance and marriage between an American Armenian girl and her immigrant husband who survived the 1915 Armenian Genocide in Turkey. In the aftermath of the Genocide from the twenties to the early seventies, the couple and their three children become vivid, quintessentially American characters, only for tragedy to find them again in a staggering echo of the genocide. Combining history and fictionalized memoir, The Ash Tree is an important, beautifully written novel of survival, new life, and heartbreak. Short-listed for the William Saroyan International Writing Prize from Stanford University.

Assessment:

Armen emigrates to California after the 1915 Armenian genocide. He meets and marries Artemis and they raise two sons and a daughter. Family is the focal point of this tale of an Armenian experience that spans 1925 to 1972 in the U.S., a rich soup of custom, family, and community. This is a character-driven work and the writing effectively captures the nuances of a singular community. The novel would, however, benefit from some tightening, particular during expository passages.

Date Submitted: September 18, 2016

THE ASH TREE – a novel – by Daniel Melnick. West of West Books, 2015. 302 pgs. $25.

Review by Paula Bloch

Armenian Mirror Spectator - October 10, 215

[Paula Bloch is a retired advisor, administrator, and teacher at Cleveland State University.]

Commemorations are a fixture in our public lives. We mark dates to call to mind a particular event or to teach a new generation the importance of a momentous occurrence. Much was made in the general media in late April of the Armenian Genocide of 1915; however, the public remembrances were fleeting – a quick story in the nightly television or radio broadcast or a newspaper story. Adding to the fragility of the stories is that this is a centenary remembrance; most, if not all, of the eyewitnesses are gone. Who will re-tell the facts and explore the ramifications of early twentieth century tragedies? Both historians and fiction writers offer different approaches and perspectives.

One such narrative is Daniel Melnick's THE ASH TREE which strikes a delicate balance between history and fiction. Permeating the book are references to actual events and places. And to sensory memories of “plump oil-cured olives in Constantinople…anchovies, the brine washed off [having] the savor of a kiss…and oranges [tasting] of sunlight and the tree.” The sense of place is strong, whether Turkey, Armenia, or California and Fresno.

A basic timeline of the book takes one family from 1915 to 1972. The prologue, however, opens in 1972 California with a death in the family of Armen and Artemis Ararat. This violent death ruptures their world. It will take the rest of the story to explore why this death occurred and to understand the characters who inhabit this world.

Although both from Armenian families, Armen Ararat and Artemis Haroutian are of different temperaments and outlooks. When we first meet Armen, he witnesses neighbors and teachers being killed in Turkey. Some 10 years later as a student at Berkeley, he remembers his European past and honors his relationship to it. He feels that all the immigrants had been permanently scarred by what they carried with them from Turkey. In contrast, Connecticut-born Artemis Haroutian did not want to marry a man born in the old country and “had always wanted a suitor who was free of the agony of 1915...not weighted down by foreignness and history.” These two positions haunt the characters and the novel. Melnick gives voice to the ambivalence of any group in a diaspora – to hold sacred the memory of the past and to forge a new, more hopeful life.

The strength of the novel is its careful summoning of a particular world that is the Armenian community centered in Fresno and the universality of the human inter-actions that makes this applicable to all. Early on in the novel, Armen's landlady says that what is important is that the family survives. Armen and Artemis build a life together for their children, Tigran, Garo and Juliet. They give up their early dreams of lives centered on poetry and art and focus on the difficult reality of raising a family. Although he is a recognized poet, Armen is known more for his business dealings. He struggles with the thought that his mastery of Armenian has no place in American life. Language eludes them both. We see this through Melnick's lens which does use language with sensitivity and clarity.

As the Ararat children grow, they become part of the wider world, forging relationships outside the Armenian community. Marriage and business dealings extend their boundaries. The novel takes on a more intimate and emotional layer as Juliet marries Sammy Weisberg, a young Jewish man.

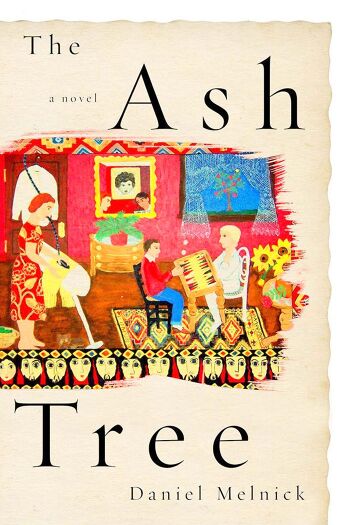

It is here that history and narrative fiction most strongly overlap. Juliet and Sammy mirror the author and his wife, Jeanette Arax Melnick whose painting is the cover art of THE ASH TREE. The Ararat family is based on the Arax family; yet, there is so much more of the interior lives of these characters inhabiting these pages.

As the novel comes full circle from 1972 back to 1972, we can see that one death can stand for all losses and bereavements. Geography cannot change the fragility of life, but memory helps to offer solace. Daniel Melnick honors both those who know Armenian loss and those who wish to understand such losses in our lives generally.

10/16/2015 Cleveland

Cleveland author honors memory of Armenian Genocide with new novel

Beachwood resident Daniel Melnick's latest novel, "The Ash Tree," chronicles an Armenian-American family beginning with the 1915 Armenian Genocide. Historians estimate that 1.5 mllion Armenians perished in the Genocide, which created an Armenian diaspora and resulted in a number of vibrant Armenian-American communities. Melnick. 71. explores its impact on an Armenian famiy over generations and decades. (John Petkovic/The Plain Dealer}

[http:1/connect.cleveland.com/staff/jpetkovi/index.html ] By John Petkovic, The Plain Dealer [http:/lconnect.cleveland.com/staff/jpetkovi/posts .html]

CLEVELAND, Ohio -- Processions of refugees wander the desert of Syria - defeated and lost, desperate for some safe passage under a beating sun as pitiless as the world around them.

It is a familiar scene, one we have come to witness on a daily basis. But this particular scene is not from the Syrian civil war, 2015.

It is 1915, a year that brought the Armenian Genocide. Historians estimate that 1.5 million were systematically killed by Ottoman Turks [http://wn"lv.nytimes.com/ref/timestopics/topics_armeniangenocide.html] . It began one evening with the rounding up and killing of Armenian intellectuals in Constantinople and included the forced death march of hundreds of thousands into the Syrian desert.

The Armenian Genocide led to the creation of a vast diaspora, with vibrant immigrant communities taking root in America . It is also the invisible character that shapes and haunts "The Ash Tree" (West of West Books, 302 pp, $25).

Beachwood resident Daniel Melnick's latest novel spans decades and generations to chronicle an Armenian -American family. "\'Vhile the book opens in 1972, in California, it quickly reaches back to 1915, to the crumbling Ottoman Empire.

Or, more precisely, the memory of 1915 - since memories of traumatic events are as vital to the events themselves in "The Ash Tree."

"Memory is a very crucial thing to me, and the status of memory is central where there is this huge trauma," says Melnick, who will do a reading at Mac's Backs in Cleveland Heights at 7 p.m. Thursday, Oct. 22. "It impinges on each of the characters and directly on the consciousness of Armen."

That would be Armen Ararat, the central figure in "The Ash Tree." His life spans the entirety of the novel, beginning as a youth when he witnesses the corpses of 20 Armenian men hanging from the gallows under the supervision of Turkish gendarmes and soldiers.

We are quickly pulled forward 10 years to Berkley, California - where Armen is a student living with an Armenian landlady, Madame Hagopian, whose husband was one of the 20 men who perished that night.

"There's hardship, even starvation, I know, but there is hope," she says, exuding a world-weary yet stubborn belief that the endangered must somehow stick together to survive.

It's an ongoing theme - one that comes with great tension in "The Ash Tree."

You see, this is a story not about the Armenian-American per se. Rather, it is an exploration of the hyphen in between "Armenian" and "American" - the struggle, the road, that existential purgatory that lies between the Old World and the "American Dream."

"So much of our culture is focused on identity politics, but what is often overlooked is the struggle to find identity," says Melnick, a Jewish American and a retired Cleveland State University literature professor who continues to teach at Case Western Reserve University.

"It is a genuine ongoing tension in not just the Armenian-American but also in other communities," he adds, "where you have people that want to retain a connection and some that want to wash their hands of it."

Melnick, 71, based "The Ash Tree" on his family and the community he encountered through his ,cife, Jeannette Melnick (nee Arax). Her painting, depicting a family on a fraying tapestry, is on the cover of the book.

"The Armenians have the fragile status of a dispersed people, and you suddenly had hundreds of people settling in places - some you wouldn't imagine, like Fresno," he says, referring to the his wife's hometown. "And yet Fresno had a lot of same qualities of the lands they left behind."

The central California city became a magnet for Armenian farmers in part because of its Mediterranean-like soil and weather.

"You could plant anything in Fresno and it could grow, just like back home," says Melnick. "And the other thing is about Fresno is that it was this farmland, this city in the desert on the edge of the civilized world. It was the Wild West, with different people settling there from Mexico to farm and harvest - a collision of cultures, with a wildness and anarchy that wasn't that different from home."

So close, yet so far away - 7,000 miles, that is.

As Armen, who pens poetry before assuming the life of a farmer and businessman in Fresno, writes: "In exile, I cannot forget."

America might be his place of exile, but it is home to his eventual wite, Artemis. And as a girl, the Connecticut-born Armenian-American dreamed of marrying an American-born man. She wanted to be free from the specter of 1915.

Negotiating the push and pull of the Old and New worlds is common in immigrant families, even generations later. But it is particularly acute in the Armenian -American community, says Melnick.

Not just because of the genocide, but also because of the ongoing struggle to have it recognized.

While France, Russia, Canada and Brazil and 40 other countries around the world have officially recognized the Armenian Genocide, United States still has not, due to pressure and threats from Turkey, which denies that the genocide took place.

"Armenians feel that it's a terrible mistake and injustice that the American government allows Turkish denials to continue," says Melnick.

The grievance has been a uniting cultural force within the Armenian community, though it has also led to political divisions -- which are explored in "The Ash Tree."

"Armen is a lefty - and there were many in the Armenian community that saw the Soviet Union as a protector of Armenia," say Melnick, referring to Armenia's absorption into the U.S.S.R., in 1922. "On the right, there were those opposed to Stalin, so you have a very complicated feelings and complex situations."

Divisions surrounding big events resonate throughout "The Ash Tree," even as it culminates in the turbulent 1970s, when militant and clandestine groups dominated American and European politics.

That's not to say that "The Ash Tree" is a historical or a political novel.

"While there are historical markers and political threads throughout the story, I'm more interested in how people cope with big events," says Melnick.

George Santayana is famous for saying, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." Yet it is a half-truth - for we are often overtaken by the past even if we remember it all too well.

When I started thinking about this story, I wanted this to be a monument to the Armenians," says Melnick. "But the idea of the hyphenated person resonates with so many different people that connect it with their lives and experiences and how they have dealt with memory and history."

Melnick released the book for the centennial of the Armenian Genocide to underscore both the memory and the history. "The irony is that it correlates with the massive exodus of Syrians," he says. "One hundred years later... it is haunting."

© 2015 Northeast Ohio Media Group LLC. All rights reserved