Society is fractured. Life for most is a desperate struggle. Natural resources are scarce, and the discovery of a miracle source of new, clean energy only serves to deepen the cracks. As the planet reaches breaking point, the sudden appearance of two mysterious pillars...

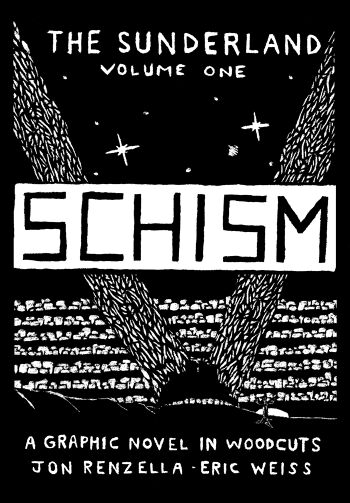

“The Sunderland Volume One: Schism” is the first in an epic trilogy of graphic novels set in a dystopian world. It will be followed by “Solitude” and “Thermidor.” This is quite an ambitious work and I salute, artist Jon Renzella and writer Eric Weiss, the talent behind this 450-page book of black and white woodcuts and text.

From the introduction:

Society is fractured. Life for most is a desperate struggle. Natural Resources are scarce and the discovery of a miracle source of new, clean energy only serves to deepen the cracks. As the planet reaches breaking point, the sudden appearance of two mysterious pillars…

It’s a very intense and vivid world that Renzella and Weiss have created. If you enjoy comics with a social commentary bite to them, then this is something you’ll want to check out. The creators of this book live and work in Taiwan and so it is interesting to keep that in mind as a subtext.

The Green movement is in disarray. The average citizen doesn’t stand a chance. And the Petrolol corporation just keeps chugging along. The narrative can be rather dense at times and so can the artwork, but it grows on you. This is a byzantine journey crowded with numerous characters confronting chaotic and enigmatic challenges. There is no hero. There is no clear resolution in sight. The story just is. But out of that jungle we find numerous graceful and poetic moments.

“Schism: The Sunderland, Volume One” is published by Lei Press and printed in Taiwan. It is available through Jon Renzella’s website. You can find it right here.

Society is fractured. Life for most is a desperate struggle. Natural Resources are scarce and the discovery of a miracle source of new, clean energy only serves to deepen the cracks. As the planet reaches breaking point, the sudden appearance of two mysterious pillars…

Schism is the first volume in The Sunderland trilogy of graphic novels by Jon Renzella in conjunction with Eric Weiss that addresses the tribal nature of humans - and it is made up entirely of woodcuts.

Speaking as someone who has attempted making woodcuts a couple of times, I can tell you that the process is a gruelling one. Wood isn't as malleable as lino, not as soft, so every cut must be made with precision, a delicate balance of force and control. The fact that all 450 pages of Schism were formed as woodcuts is staggeringly impressive - and no little wonder that it took a full two and a half years of daily toil to make.

Renzella, the creator of the series, is an American artist and printmaker living in Taichung, Taiwan, where he runs the non-profit Lei Gallery. His artwork brings together the busy elements of everyday life through a unique, cross-cultural lens, as can be seen in his large-scale installation, Lost in Taiwan.

The resulting style is very bold and unapologetic, and Renzella's creative flair shines through in the volume's often surreal (or drug-fuelled) 'interludes' and landscapes, with the images and compositions ranging from beautiful to rather disturbing.

The first thing that struck me when I started reading the book, beyond the images, was its tongue-in-cheek humour - for example, the naming of Rupert Tits, spokesperson of extractives company Petrolol. The characters are presented in a similarly sardonic fashion, with the religious zealot/professional swindler Dr Stella Von Mite depicted with absurd hair and a dopey expression as she appears on television to assure followers that they need only to send her money to ensure their salvation.

Much of the story takes place on the BUH People's News in the form of interviews and dialogue, and the text is at times dense and imposing, much like the clear-cut contrast of the black-and-white prints. The portrayal here is of a world divided into sects, with the media acting as a major influencer of public opinion, as of course it is in reality, and the facilitator of discussion between the other groups - interspersed, naturally, with adverts favouring the highest bidder. Meanwhile, the interviews are little more than opportunities for posturing from all sides - the military, resource tycoons, ecologists and so on.

"Everyone was so dug in that there was virtually no middle ground to find. Because the attendees were, largely, the most vocal and radical members of society, conversation consisted of grandstanding and shouting past one another."

- Schism

Each group stands opposed to the others in a fractured, distrustful society.

"The idea for the structure of the story came more from internet culture, and the idea that people can find their own groups online and never stray from them," Renzella tells me. "Group thinking and confirmation bias emerges from not accessing different viewpoints, and this is the thinking behind the Schism, the fracturing of society into isolated, like-minded subcultures. When the Conduits appear, each group 'knows' where they came from, and use their explanation to reinforce their worldviews.

"I'm surrounded by an ever-changing community of expats, most of whom have travelled extensively, which proves quite a contrast to growing up in a place where most people never leave the country. This combined with my own travels has given me many opportunities to think about and explore this idea of institutional or cultural 'knowledge', and driven home the importance of questioning assumptions."

Oddly enough, I wrote something similar on the subject of feminism for issue 20 of Global: the international briefing around Christmas last year (and I hope you'll excuse me quoting my own writing here…):

There is a big problem with just labelling oneself as a something-ist, because once this happens the something-ism becomes part of one's identity … Instead of continuing to exist as a person with millions of individual ideas, one's identity becomes compartmentalised into set parts - feminist, capitalist, vegetarian - each of which have their own assumed beliefs and ideas. What this means is that it's easy for a person to find themselves defending issues that they don't personally agree with simply on a misguided principle. Everything else becomes the evil 'other' that should not even be considered.

This submergence in group identity in which the loudest rule can easily lead to a distortion of ideas or a loss of personal perspective. It becomes harder and harder to identify the flaws in one's ideology and the urge to defend such flaws increases. And this is a problem.

The narrative jumps from one faction to another, introducing the ideology and nature of each in light of resource scarcity, ecological issues and the schism itself - the moment that society ruptured and each group went its own way, making up its own ideology and ethics en route. It's a piece of social commentary that is always relevant, whether you see the real-life divisions as lines on a map, in terms of profession or, as Renzella points out, online - on social media sites like Twitter and Facebook, where you can choose to see updates only from likeminded people; on Google, which alters your search results based on your search history.

At a time when more information than ever before is available to us and, simultaneously, is vetted by us or by companies into conforming to the beliefs that we already hold, The Sunderland is more relevant than ever.

The Sunderland Vol. 1 - Schism is due to see a new print run in September and can be purchased through Renzella's site.

I received a copy of this book in exchange for an honest review.

The world is torn into radically divergent societies after the economy collapses in Renzella and Weiss’ stark graphic novel debut.

In the near future, the Earth’s fuel reserves will run out within a decade, but the discovery of a new energy resource promises fuel for the next 75 years. Environmental activists who oppose the corporation Petrolol’s essentially strip-mining this resource from Earth are elated about a second discovery of a clean power source. But the announcement of this find has detrimental results—Petrolol is rendered worthless, which, in a peculiar turn, causes the economy to crash. Many people become homeless and experience violent storms and a mysterious virus. The world ultimately splits into diverse groups that seem to be on the brink of war. Scientists conduct experiments in the Towers; the military hides away in subterranean bunkers; and worshippers of the Earth goddess, Pachamama, isolate themselves in eco-domes. The military has a mole embedded in the latter group (often called “the Hippies”) while also infiltrating followers of Serin Civetta, a zealot who’s convinced many that reptilian aliens are behind Earth’s devastation. But aliens are just one possible explanation of the sudden appearance of two new towers that soar above the existing Towers. Or they may be, as the military surmises, weapons. The tale is a scathing commentary on societal divides, whether politically or religiously motivated. Much of the narrative occurs as flashbacks, with events leading to what’s known as the Schism. As this is Volume 1, months preceding the Schism are left unexplored, while a gleefully perplexing conclusion sets the stage for proposed later installments. Despite text unaccompanied by word balloons, strong, distinctive dialogue makes it easy to comprehend who’s speaking each line. Nevertheless, the book’s most accomplished feature is Renzella’s unique woodcut illustrations. Broad, bold lines still manage nuance, including clear facial expressions, while thoroughly filling pages with artwork.

A well-imagined adventure coupled with striking black-and-white imagery.

A haunting and ambitious dystopia about a familiar land, which may or may not be our world, in which society collapses in various ways all too plausible...

Grand in scope, the narrative covers institutions ranging from environmentally-destructive industry to the military industrial complex and emerging religious cults. There is no main protagonist, but a shifting point of view which takes the reader throughout this setting. There's the media, then poor cult members and conspiratorial documentarians trying to make sense of the collapse.

The art, completely made from woodcuts, is amazing and perfect. It is truly a feat to construct an entire (and lengthy) graphic novel in this fashion. The ambition is something to appreciate, however it does make for a story--if that's what this is--hard to follow at times. It's all to big for one character's arc, it's about the nation and the world as a whole.

Even if constructed in vignettes, these satires are quite successful at getting to the heart of something deeply wrong in the world. If this sounds pessimistic, it is, but also don't get me wrong as this satire can be legitimately funny at times.

The ending is sudden, and I look forward to Jon Renzella's sequel and completion of the trilogy as long as it takes. The art alone, dark and moody and somehow simple, is assuredly not to be rushed.

As a fan of graphic novels, I leapt at the opportunity to read Jon Renzella and Eric Weiss’ Schism, which makes a nice change of pace from reviewing simply prose. The art, in pure black and white with no grey, by Renzella is a sight to behold, absolutely arresting, and built from woodcuts. Throughout, very few individual panels make up the pages, and often these run together to paint a larger picture, and oftentimes, it presents absolutely beautiful double-page spreads. The result is otherworldly, but also off-kilter, conveying a strange undercurrent before you even get to the words.

Yet, the words here are important, and also do much of the heavy lifting. Unlike the majority of graphic novels, Renzella and Weiss pack Schism full of words; instead of relying on speech with the occasional captions, its writing is denser than you ordinarily find in the medium, and provides a lot of prose. Yet, at its 450 pages, this is still a fairly brisk read: if the images had been condensed to something more akin to most graphic novels and comic books out in the wild, this could fit into a couple of hundred pages.

(Follow the link to read the full review, as well as a review of The Sunderland Volume 2: Solitude)