Assessment:

Idea: A detailed and engaging story that offers readers great insight into days of yore life in Iceland. The author delves far back into his family history, which is in essence an adventure story. Oftentimes, family chronicles, particularly those with unfamiliar names, are a tedious bore. Not so in Sigurdsson's capable hands. There is so much here to experience and enjoy, particularly the photos, which greatly enhance an already captivating storyline.

Prose: Beautifully written, this work is a pleasure to read. The author is able to make his subjects come alive, even those from distant ages. Succinct yet detailed, it feels as if the author carefully selected each word.

Originality: This work takes a distinctive and original approach to Viking history, interweaving his family story with his own journey to offer readers a unique perspective.

Character/Execution: The author does a fine job bringing all his players to life, from his ancestors to himself on his life journey. It's because of this skillful ability that the reader stays engaged and interested throughout the work.

Blurb: Captivating and entertaining, this work offers readers entrance into a whole new world. Readers will savor each story as they travel with Sigurdsson as he recounts fascinating family tales and chronicles his own life journey.

Date Submitted: January 12, 2022

"Whether you're a seasoned tourist or an armchair traveler with Iceland on your mind, you'll want to start by reading Viking Voyager, an account of place and people no tourist guide can provide. This is the real stuff: growing up in a stark landscape of fjords and volcanoes, where harsh winters and seafaring disasters lurk in the legacy, where resourcefulness, stoicism, hard work, and family loyalty are prized, and where, like the Saga heroes, youth are expected to make their way abroad as a test of courage and ingenuity. This is Sverrir Sigurdsson's story, an extraordinary tale of what it means to be Icelandic, how tenacity of spirit enabled a small country to navigate its way through hardship and war to contribute on the larger stage of human endeavors. Beautifully written with a fast-paced narrative style, Viking Voyager is essential reading for any adventure-seeking tourist in the 21st century."

Icelanders prize boldness, adventure and self-improvement through working in faraway lands. They call timid souls who never stray far from their birthplaces “heimskur,” which translates as both “homebody” and “stupid.”

“A heimskur has never left home and therefore is looked down upon as not having fulfilled his potential,” said Iceland native and Vienna resident Sverrir Sigurdsson.

Steeped in 13th-century sagas of adventure and derring-do, Sigurdsson early in life vowed to cast his life’s net far afield and do his ancestors proud.

Sigurdsson and his wife, author Veronica Li, recently published “Viking Voyager: An Icelandic Memoir,” which combines Sigurdsson’s life story with lively travelogues and dollops of Icelandic history and culture. In one, he describes the country’s putrified-shark delicacy, hákarl, as tasting like “blue cheese marinated in ammonia.”

The book was about two decades in the making. Li encouraged her husband to write about his multi-faceted life and stress the theme of his being a modern-day Viking.

“You can take a person out of a place, but not the place out of a person,” Li said. “He was still a Viking through and through.”

Sigurdsson, still trim and fit at age 82, grew up in Reykjavík, went to Finland after high school to study architecture and embarked on a three-year plan to work in foreign lands.

Sigurdsson, who in addition to Icelandic and English speaks Danish, Swedish and German, struggled with Finnish until he worked in an architectural office where his co-workers spoke only that language. After 30 days of their banter and encouragement, Sigurdsson was stunned when he understood an entire conversation of office gossip. The Finns then embraced him like a brother, Li said.

“I became one of them, absolutely,” Sigurdsson said. “They thought of me as one of their own.”

He intended to return home to Iceland to help improve that country, but work opportunities led him to spend more than a half-century overseas.

After Finland, Sigurdsson worked in the Middle East. Assigned to write a report in English while working in Kuwait, he read Agatha Christie mysteries to master what he considered to be a “scrappy, undisciplined language.”

Sigurdsson spent the last 25 years of his career with the World Bank, where he built schools all over the globe and enhanced the availability of textbooks. An early computer user, he chafed at the organization’s inflexible bureaucracy, but thrived following a Reagan-era reorganization of the bank.

His career experiences taught him to deal with people from many backgrounds and understand their culture and living environment, he said.

Sigurdsson has visited between 50 and 60 countries and worked in about 30 on five continents. He marveled at desert landscapes in the Middle East, gaped at wildlife in Africa and recoiled at horrific segregation in apartheid-era South Africa.

He has lived in the U.S. for several decades and said he likes the country’s openness and freedom to build his own house, which would have been heavily regulated in Iceland. Living in the Washington, D.C., region puts him within a five-hour flight either to his native country or to California, where Li’s family lives.

The book begins with the tale of a fishing vessel that sank in 1910 with some of Sigurdsson’s ancestors on board. The country was poor and underdeveloped then, having long been a Danish colony and subjected to lopsided trade agreements.

Iceland’s fortunes changed in World War II. Both the Germans and British understood the island nation’s strategic value, and the Allies worried the Germans might hop from Nazi-controlled Denmark and Norway to Iceland and then on to Greenland, Canada and eventually the U.S.

On May 10, 1940, the same day German forces attacked the Netherlands and Belgium, the British sent an invasion force to Iceland and their troops began pouring into the country – to the delight of Iceland’s women and chagrin of its men. U.S. troops followed later in the war, and afterward built a major naval airbase south of Reykjavík.

Economic development improved precipitously after World War II, but other changes have followed. Iceland’s youths are fleeing laborious farm work for steady jobs in cities ,and many farms have been converted into bed-and-breakfasts. English usage is pervasive and many youths view Icelandic as an archaic language, Sigurdsson said.

“Our mother tongue is under threat,” he said.

Iceland still has only about 360,000 residents, or one-third of Fairfax County’s population, but welcomes approximately 2 million tourists annually. The country imports workers from Poland, Lithuania and Latvia to handle the tourism crush.

“Viking Voyager” won a Red Ribbon at the 2020 Wishing Shelf Awards and was a finalist at the Independent Author Network’s Book of the Year Awards.

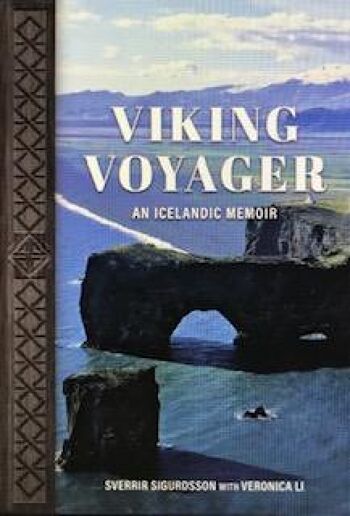

The decorative pattern on the cover’s border is from wooden furniture carved by Sigurdsson. The cover also shows stunning seaside rock formations at Dyrhólaey, Iceland, near where he spent summers as a youth doing farm work.

Tales of Sigurdsson’s childhood give readers a deeper understanding of Iceland, said Inder Sud, former president of the 1818 Society, a World Bank retiree group.

“Sigurdsson’s description of his experiences growing up in Iceland allows you to get inside the culture of the country, particularly its unique, self-reliant, minimalist and hardy national character,” he said.

McLean author Dorothy Hassan, who did a final edit of the book, enjoyed its tales of Iceland’s bracing winters and Sigurdsson’s adventures.

“‘Viking Voyager’ offers a fascinating glimpse into Sverrir’s often tough upbringing in Iceland, which was relatively underdeveloped until set on a more prosperous path by Allied bases during World War II,” she said. “Like his forbears, this Viking returned to his homeland several times, but the winds of change always blew him offshore once more, finally back to Northern Virginia.”